Supervision for Texas LPCs with Supervisor Status (6 hours)

Introduction

There are two parts to this course: 1) The text and; 2) The quiz. BE SURE TO CLICK THE ARROW AT THE VERY END OF THE TEXT OR REFERENCE SECTION TO RECEIVE CREDIT FOR HAVING READ THE TEXT (PART ONE). THE ARROW WILL BE ON THE BOTTOM RIGHT OF THE PAGE.

The BHEC indicates that the Supervisor status isn’t a type of license. Rather, it designates an LPC who is approved by the board to supervisor LPC-Associates.

Texas Licensed Professional Counselors with Supervisor status (LPC-S) are authorized to provide the supervision LPC-Associates need to fulfill the 3,000 hours of supervised experience required for full licensure as Texas Licensed Professional Counselors (LPC). According to Texas Administrative Code Rule 681.92, LPC Associates must complete supervised experience acceptable to the Texas Behavioral Health Executive Council of 3,000 clock-hours under a Council-approved supervisor (LPC-S).

According to TAC Rule 681.141, licensed professional counselors holding the supervisor status (LPC-S) must complete six hours of continuing education in supervision and that count towards the 24 hours required each renewal period of all Texas Licensed Professional Counselors. The purpose of this course is to provide the six additional hours of supervision required for license renewal for Texas Licensed Professional Counselors holding the supervisor status (LPC-S).

There are currently 6,000 LPCs with supervisor status and approximately 5,000 LPC Associates in Texas. This ratio implies there are probably many LPC Supervisors not currently supervising any Associates, but who see the value in having the Supervisor status for many reasons including an employer, or future employer, requiring it to accommodate supervision needs of other employees working on full licensure. Even when supervisors do not supervise Associates, the status is an indication the licensee has been licensed for at least five years.

Statutes and Rules for LPC-Supervisors

The Texas Administrative Code, Chapter 681 (Professional Counselors), Subchapter C (Application and Licensing), Rules 681.91, 681.92 and 681.93, provide the bulk of guidelines for LPC Supervisors and the Associates they supervise.

LPC Supervisors should be aware that the rules found in the TAC change periodically, so these requirements should be verified with the most recently published guidelines found at the Texas Secretary of State website.

Many licensees may choose to use the Consolidated Rulebook for Professional Counseling as a reference for rules. It is found at the Texas Behavioral Health Executive Council (“Council”) website. When using the Rulebook, the Council advises:

As a courtesy to the public, BHEC agency staff have consolidated the various rules applicable to each profession into an easy-to-use rulebook available for download as a portable document format (PDF) file.

The BHEC indicates that, while the Council makes every reasonable effort to update and maintain the accuracy of these rulebooks, due to the evolving nature of the law and limited time and resources, the rulebooks may not reflect the current state of the law.

You are cautioned against relying solely upon these rulebooks and urged to review the current rules which are available through the links below. Moreover, if a conflict exists between a rulebook and the rules published on the Secretary of State’s website, the version on the Secretary of State’s website shall control. Compliance with the law cannot be excused due to an outdated, mistaken, or erroneous reference in a rulebook.

Notification of Rulemaking and Texas Register

The Council publishes all of its proposed, adopted, withdrawn and emergency rules in the Texas Register in accordance with the Administrative Procedure Act. Any proposed, adopted, withdrawn or emergency rule action taken by the Council can be viewed online via the Texas Register.

REQUIREMENTS of TAC RULES 681.91, 681.92, and 681.93:

One of the most important responsibilities of being a Licensed Professional Counselor with Supervisor status is staying informed of the statutes and rules applicable to licensees, Supervisors, and Associates.

Although some of the statutory requirements for LPC Supervisors are separate and distinct from those of LPC Associates, there is substantial overlap in many duties as codified in TAC RULES 681.91,681.92, and 681.93.

LPC Supervisors should be aware of all requirements specific to both them and supervisees since questions relevant to these statutes and rules will inevitably arise in the supervision process. The Supervisor carries responsibility for ensuring the Associate has received instruction on the statutory requirements the Associate must fulfill.

According to Rule 681.93; 1) Supervisors must review all provisions of the Act and Council rules in this chapter during supervision, and (2) The supervisor must ensure the LPC Associate is aware of and adheres to all provisions of the Act and Council rules.

The following highlights many of the required tasks and documents mentioned in Rules 681.91, 681.92, and 681.93:

RULE 681.91

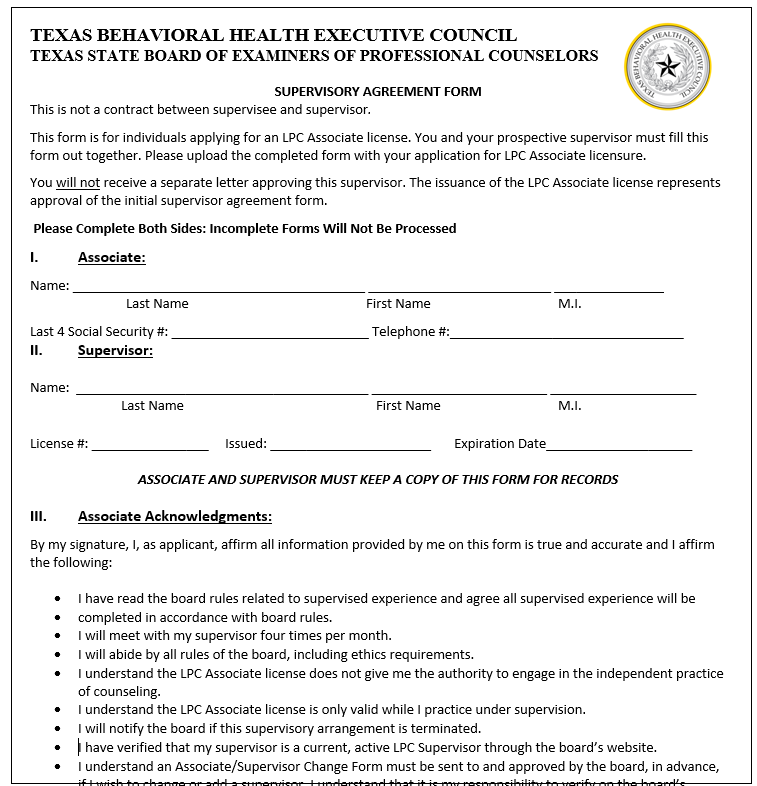

►The LPC Associate enters into a supervisory agreement with a Licensed Professional Counselor Supervisor (LPC-S); and has not completed the supervised experience described in §681.92 of this title (relating to Experience Requirements or Internship). Comments: This reiterates the idea that LPC Associates cannot complete any supervised experience in Texas unless it is through an approved supervisor and the approved supervisor cannot sign-off on any hours completed before the supervision agreement began and was approved by the Board. The Supervisory Agreement form can be found at the BHEC website under Forms and Publications. The top of the first page looks like this:

►An LPC Associate must comply with all provisions of the Act and Council rules. Comments: LPC Associates are bound to the same ethical standards of fully licensed professional counselors when applicable.

►To practice counseling in Texas, a person must obtain an LPC Associate license before the person begins an internship or continues an internship. Hours obtained by an unlicensed person in any setting will not count toward the supervised experience requirements. Comments: The Supervisor Agreement Form is sent in with the application for LPC Associate licensure. Issuance of the LPC Associate license indicates the Supervisory Agreement and Supervisor have been approved. A separate notification of approval is not sent to the supervisor.

►An LPC Associate may practice counseling only as part of his or her internship and only under the supervision of a Licensed Professional Counselor Supervisor (LPC-S). The LPC Associate shall not engage in independent practice. Comments: TAC 681.2 defines independent practice as the practice of providing professional counseling services to a client without the supervision of an LPC-S. All Associates have to be under supervision by a LPC-S.

►An LPC Associate may have no more than two (2) Council-approved LPC supervisors at any given time. Comments: The limitation of having no more than two supervisors was implemented in the TAC in 2013. Apparently, there was no limit prior to this time. However, Associates who have even two supervisors could potentially encounter some of the same issues of clients seeing two therapists concurrently; there could be disagreement between the supervisors. This potential conflict or difference of opinion might especially be relevant in regard to the theoretical approach used by a supervisor.

►An LPC Associate must maintain their LPC Associate license during his or her supervised experience.

►An LPC Associate license will expire 60 months from the date of issuance.

►An LPC Associate who does not complete the required supervised experience hours during the 60-month time period must reapply for licensure.

►An LPC Associate must continue to be supervised after completion of the 3,000 hours of supervised experience and until the LPC Associate receives his or her LPC license. Supervision is complete upon the LPC Associate receiving the LPC license.

►The possession, access, retention, control, maintenance, and destruction of client records is the responsibility of the person or entity that employs or contracts with the LPC Associate, or in those cases where the LPC Associate is self-employed, the responsibility of the LPC-Associate. Comment: Some have argued that self-employed LPC Associates who have control of client records may limit a supervisor’s access to them. Also, allowing Associates to be self-employed may require the supervisor to be responsible for issues beyond their expertise such as aspects of running a business, and generally create a greater workload for supervisors. Others have supported this rule believing it to open up new opportunities for rural residents to receive quality counseling services by attracting more licensees to those communities, provide potential financial benefit to Associates, and create greater parity with other licensed mental health professions. Please refer to the Texas Register Preamble for a more detailed explanation for the reasoning behind the adoption of this rule.

►An LPC Associate must not employ a supervisor but may compensate the supervisor for time spent in supervision if the supervision is not a part of the supervisor’s responsibilities as a paid employee of an agency, institution, clinic, or other business entity.

►All billing documents for services provided by an LPC Associate must reflect the LPC Associate holds an LPC Associate license and is under supervision.

►The LPC Associate must not represent himself or herself as an independent practitioner. The LPC Associate’s name must be followed by a statement such as “supervised by (name of supervisor)” or a statement of similar effect, together with the name of the supervisor. This disclosure must appear on all marketing materials, billing documents, and practice related forms and documents where the LPC Associate’s name appears, including websites and intake documents.

RULE 681.92

►All applicants for LPC licensure must complete supervised experience acceptable to the Council of 3,000 clock-hours under a Council-approved supervisor. Comment: The BHEC has been asked about decreasing the 3,000-hour requirement. In essence, the BHEC does not adopt rules that conflict with the Texas Occupations Code. The specific BHEC response is found in the Texas Register, Preamble, as follows: The 3,000 hours of supervised experience needed for licensure is required by statute, see §503.302(a)(4) of the Occupations Code, therefore this agency declines to reconsider this requirement or shorten it. The Council declines to amend the licensing requirements for an LPC or LPC-Associate, the Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors has not articulated a need to amend the licensure requirements because of these rule amendments.

►All internships physically occurring in Texas must be completed under the supervision of a Council-approved supervisor.

►For all internships physically completed in a jurisdiction other than Texas, the supervisor must be a person licensed or certified by that jurisdiction in a profession that provides counseling and who has the academic training and experience to supervise the counseling services offered by the Associate. The applicant must provide documentation acceptable to the Council regarding the supervisor’s qualifications.

►The supervised experience must include at least 1,500 clock-hours of direct client counseling contact. Only actual time spent counseling may be counted. Comments: The BHEC Rules define “direct hours” as “time spent counseling clients.” Indirect hours are defined as time spent in management, administration, or other aspects of counseling service ancillary to direct client contact.

►An LPC Associate may not complete the required 3,000 clock-hours of supervised experience in less than 18 months.

►The experience must consist primarily of the provision of direct counseling services within a professional relationship to clients by using a combination of mental health and human development principles, methods, and techniques to achieve the mental, emotional, physical, social, moral, educational, spiritual, or career-related development and adjustment of the client throughout the client’s life.

►The LPC Associate must receive direct supervision consisting of a minimum of four (4) hours per month of supervision in individual (up to two Associates) or a group (three or more) setting while the Associate is engaged in counseling unless an extended leave of one month or more is approved in writing by the Council approved supervisor. No more than 50% of the total hours of supervision may be received in group supervision.

►An LPC Associate may have up to two (2) supervisors at one time.

RULE 681.93

► A supervisor must keep a written record of each supervisory session in the file for the LPC Associate. The supervisory written record must contain:

• a signed and dated copy of the Council’s supervisory agreement form for each of the LPC Associate’s supervisors;

• a copy of the LPC Associate’s online license verification noting the dates of issuance and expiration;

• fees and record of payment;

• the date of each supervisory session;

• a record of an LPC Associate’s leave of one month or more, documenting the supervisor’s approval and signed by both the LPC Associate and the supervisor;

• a record of any concerns the supervisor discussed with the LPC Associate, including a written remediation plan as prescribed in subsection (e) of this section; and

• a record of acknowledgement that the supervisee is self-employed, if applicable.

• The supervisor must provide a copy of all records to the LPC Associate upon request.

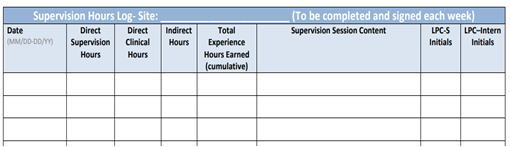

Comment: This is an example of the Supervision Hours Log found at the BHEC website under Forms and Publications that documents some of the requirements mentioned above:

► Both the LPC-Associate and the supervising LPC-S are fully responsible for the professional counseling activities of the LPC-Associate. The LPC- S may be subject to disciplinary action for violations that relate only to the professional practice of counseling committed by the LPC-Associate which the LPC-S knew about or due to the oversight nature of the supervisory relationship should have known about. Comments: The BHEC explanation found in Texas Register, Preamble: LPC-Supervisors are required to provide supervision as it relates to the practice of professional counseling by the LPC-Associate, if a matter is outside of this scope a supervisor would not be subject to a disciplinary action by the Council. For example, if an LPC-Associate decides to create a legal entity, such as a limited liability company, in Texas but fails to timely or properly file a required form or fee with Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, the Texas Workforce Commission, or any other applicable government agency, then the LPC-Supervisor would not be subject to disciplinary action by the Council for this failure by the LPC-Associate. Rule 681.92(e) requires a minimum of four hours of supervision per month for an LPC-Associate, but this is only the minimum standard supervisors can provide or require more than this minimum standard if a supervisor finds more supervision is necessary for a particular LPC-Associate.

► Supervisors must review all provisions of the Act and Council rules in this chapter during supervision. Comment: This task alone, along with much repetition and application to Associate work experience, will comprise much of what goes on in supervision.

► The supervisor must ensure the LPC Associate is aware of and adheres to all provisions of the Act and Council rules.

► The supervisor must avoid any relationship that impairs the supervisor's objective, professional judgment. Comment: this Rule (681.93 (c)) is more broad than Rule 681.42 that restricts supervisors from having sexual contact with the Associate within five years of cessation of the supervision, or of ever committing sexual exploitation or therapeutic deception of an Associate supervised by the licensee. Even after five years, supervisors can be held in violation unless certain factors are met described in 681.42.

► The supervisor may not be related to the LPC Associate within the second degree of affinity or within the third degree of consanguinity. Comments: Affinity is related by marriage. Consanguinity is related by blood. The second degree of affinity would include the supervisor’s step-children, stepmother/stepfather, mother-in-law, father-in-law (first degree) and stepbrothers/stepsisters, brothers-in-law, sisters-in-law, step grandchildren, and step grandparents (second degree). Third degree of consanguinity would include the supervisor’s spouse, children, parents (first degree), brother/sisters, half-brother and sisters, grandchildren, and grandparents (second degree).

► The supervisor may not be an employee of his or her LPC Associate. Comment: LPC-Associates are prohibited from employing their supervisor, but the LPC-Associate may compensate the supervisor (e.g. contract for supervision) if the supervision is not part of the supervisor’s responsibilities as a paid employee of an agency, institution, clinic, or other business entity.

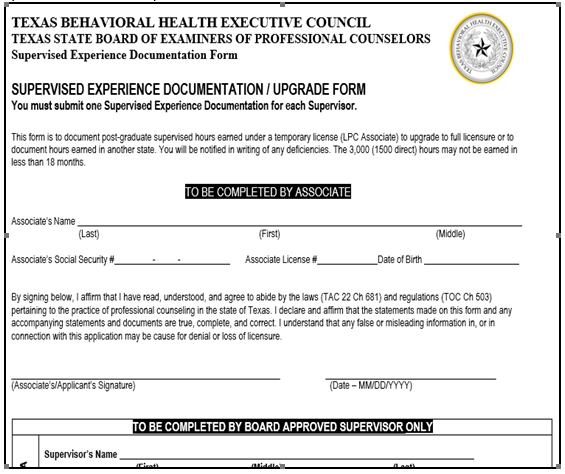

► The supervisor must submit to the Council accurate documentation of the LPC Associate's supervised experience within 30 days of the end of supervision or the completion of the LPC Associate's required hours, whichever comes first.

► If a supervisor determines the LPC Associate may not have the counseling skills or competence to practice professional counseling under an LPC license, the supervisor will develop and implement a written plan for remediation of the LPC Associate, which must be reviewed and signed by the LPC Associate and maintained as part of the LPC Associate's file.

► The supervisor must ensure the supervised counseling experience of the LPC Associate were earned: after the LPC Associate license was issued; and in not less than 18 months of supervised counseling experience.

Comment: Once the Associate has completed the 3,000 hours of experience the Supervised Experience Documentation/Upgrade Form found at the BHEC website is filled in by the Associate and Supervisor and sent in by the Associate.

► A supervisor whose license has expired is no longer an approved supervisor and: must immediately inform all LPC Associates under his or her supervision and assist the LPC Associates in finding alternate supervisors; and must refund all supervisory fees for supervision after the expiration of the supervisor status. Hours accumulated under the person's supervision after the date of license expiration may not count as acceptable hours.

► Upon execution of a Council order for probated suspension, suspension, or revocation of the LPC license with supervisor status, the supervisor status is revoked. A licensee whose supervisor status is revoked: must immediately inform all LPC Associates under his or her supervision and assist the LPC Associates in finding alternate supervisors; and must refund all supervisory fees for supervision after the date the supervisor status is revoked; and hours accumulated under the person's supervision after the date of license expiration may not count as acceptable hours.

► Supervision of an LPC Associate without having Council approved supervisor status is grounds for disciplinary action.

The Nature of Supervision

Clinical supervision by Licensed Professional Counselors with Supervisor status (LPC-S) provides one of the key ways LPC Associates acquire knowledge and skills for the counseling profession, providing a bridge between theory and practice.

Supervision is necessary in the counseling field to improve client care, develop professionalism, and impart and maintain ethical standards. In recent years, clinical supervision has become the cornerstone of quality improvement and assurance.

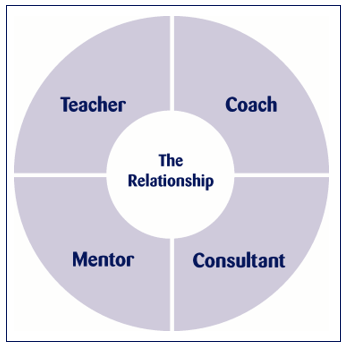

The role of an LPC Supervisor is distinct from those of counselor and administrator. Quality clinical supervision is founded on a positive supervisor–supervisee relationship that promotes client welfare and the professional development of the supervisee. You are a teacher, coach, consultant, mentor, evaluator, and administrator; you provide support, encouragement, and education to staff while addressing an array of psychological, interpersonal, physical, psychosocial and spiritual issues of clients. Ultimately, effective clinical supervision ensures that clients are competently served. Supervision ensures that counselors continue to increase their skills, which in turn increases treatment effectiveness, client retention, and staff satisfaction. The clinical supervisor also serves as liaison between administrative and clinical staff.

This course focuses primarily on the teaching, coaching, consulting, and mentoring functions of Texas LPC approved Supervisors. Supervision, like counseling, is a profession in its own right, with its own theories, practices, and standards. The profession requires knowledgeable, competent, and skillful individuals who are appropriately credentialed both as counselors and supervisors.

The perspective of this course is informed by the following definitions of supervision:

• “Supervision is a disciplined, tutorial process wherein principles are transformed into practical skills, with four overlapping foci: administrative, evaluative, clinical, and supportive” (Powell & Brodsky, 2004, p. 11). “Supervision is an intervention provided by a senior member of a profession to a more junior member or members. This relationship is evaluative, extends over time, and has the simultaneous purposes of enhancing the professional functioning of the more junior person(s); monitoring the quality of professional services offered to the clients that she, he, or they see; and serving as a gatekeeper of those who are to enter the particular profession” (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004, p. 8).

• Supervision is “a social influence process that occurs over time, in which the supervisor participates with supervisees to ensure quality of clinical care. Effective supervisors observe, mentor, coach, evaluate, inspire, and create an atmosphere that promotes self-motivation, learning, and professional development. They build teams, create cohesion, resolve conflict, and shape agency culture, while attending to ethical and diversity issues in all aspects of the process. Such supervision is key to both quality improvement and the successful implementation of consensus and evidence-based practices” (CSAT, 2007, p. 3).

Rationale

For hundreds of years, many professions have relied on more senior colleagues to guide less experienced individuals in their crafts. This is a relatively new development in the counseling field, as clinical supervision was acknowledged as a discrete process with its own concepts and approaches only within the last twenty or thirty years.

As a supervisor to the client, Associate, and possibly the organization, the significance of Licensed Professional Counselors with Supervisor status is apparent in the following statements:

• Organizations have an obligation to ensure quality care and quality improvement of all personnel. The first aim of clinical supervision is to ensure quality services and to protect the welfare of clients.

• Supervision is the right and obligation of all LPC Associates and has a direct impact on their development and the services they provide the public.

• Supervisors oversee the clinical functions of Associates and have a legal and ethical responsibility to ensure quality care to clients, the professional development of counselors, and maintenance of program policies and procedures.

• Clinical supervision is how Associates in the field learn. In concert with classroom education, clinical skills are acquired through practice, observation, feedback, and implementation of the recommendations derived from clinical supervision.

Functions of a Clinical Supervisor

The clinical supervisor wears several important “hats.” They facilitate the integration of counselor self-awareness, theoretical grounding, and development of clinical knowledge and skills; and assist in improving functional skills and professional practices. These roles often overlap and are fluid within the context of the supervisory relationship. Hence, the supervisor is in a unique position as an advocate for the agency, the counselor, and the client. You are the primary link between administration and front-line staff, interpreting and monitoring compliance with agency goals, policies, and procedures and communicating staff and client needs to administrators. Central to the supervisor’s function is the alliance between the supervisor and supervisee. Teacher, Consultant, Coach and Mentor are some of the roles a supervisor fulfills.

Your roles as a supervisor in the context of the supervisory relationship include:

• Teacher: Assist in the development of counseling knowledge and skills by identifying learning needs, determining counselor strengths, promoting self-awareness, and transmitting knowledge for practical use and professional growth. Supervisors are teachers, trainers, and professional role models.

• Consultant: Bernard and Goodyear (2004) incorporate the supervisory consulting role of case consultation and review, monitoring performance, counseling the counselor regarding job performance, and assessing counselors. In this role, supervisors also provide alternative case conceptualizations, oversight of counselor work to achieve mutually agreed upon goals, and professional gatekeeping for the organization and discipline (e.g., recognizing and addressing counselor impairment).

• Coach: In this supportive role, supervisors provide morale building, assess strengths and needs, suggest varying clinical approaches, model, cheer lead, and prevent burnout. For entry level counselors, the supportive function is critical.

• Mentor/Role Model: The experienced supervisor mentors and teaches the supervisee through role modeling, facilitates the counselor’s overall professional development and sense of professional identity, and trains the next generation of supervisors.

Roles of the Clinical Supervisor

Central Principles of Clinical Supervision

Although clinical supervision can initially be a costly undertaking for many financially strapped programs, ultimately clinical supervision can be a cost saving process. Clinical supervision enhances the quality of client care; improves efficiency of counselors in direct and indirect services; increases workforce satisfaction, professionalization, and retention; and ensures that services provided to the public uphold legal mandates and ethical standards of the profession. Central principles include:

1. Clinical supervision is an essential part of all clinical programs. Clinical supervision is a central organizing activity that integrates the program mission, goals, and treatment philosophy with clinical theory and evidence based practices (EBPs). The primary reasons for clinical supervision are to ensure (1) quality client care, and (2) clinical staff continue professional development in a systematic and planned manner. Clinical supervision is the primary means of determining the quality of care provided.

2. Clinical supervision enhances staff retention and morale. Staff turnover and workforce development are concerns for any agency, especially in recent years. Clinical supervision is a primary means of improving workforce retention and job satisfaction (see, for example, Roche, Todd, & O’Connor, 2007).

3. Every clinician, regardless of level of skill and experience, needs and has a right to clinical

supervision. In addition, supervisors need and have a right to supervision of their supervision. Supervision needs to be tailored to the knowledge base, skills, experience, and assignment of each counselor. All staff need supervision, but the frequency and intensity of the oversight and training will depend on the role, skill level, and competence of the individual. The benefits that come with years of experience are enhanced by quality clinical supervision.

4. Clinical supervision needs the full support of agency administrators. Just as treatment programs want clients to be in an atmosphere of growth and openness to new ideas, counselors should be in an environment where learning and professional development and opportunities are valued and provided for all staff.

5. The supervisory relationship is the crucible in which ethical practice is developed and reinforced. The supervisor needs to model sound ethical and legal practice in the supervisory relationship. This is where issues of ethical practice arise and can be addressed. This is where ethical practice is translated from a concept to a set of behaviors. Through supervision, clinicians can develop a process of ethical decision making and use this process as they encounter new situations.

6. Clinical supervision is a skill in and of itself that has to be developed. Good counselors tend to be promoted into supervisory positions with the assumption that they have the requisite skills to provide professional clinical supervision. However, clinical supervisors need a different role orientation toward both program and client goals and a knowledge base to complement a new set of skills. Programs need to increase their capacity to develop good supervisors.

7. Clinical supervision of Associates most often requires balancing administrative and clinical supervision tasks. Sometimes these roles are complementary and sometimes they conflict. Often the supervisor feels caught between the two roles. Administrators need to support the integration and differentiation of the roles to promote the efficacy of the clinical supervisor.

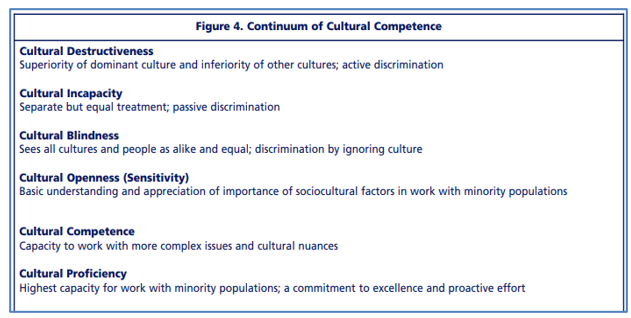

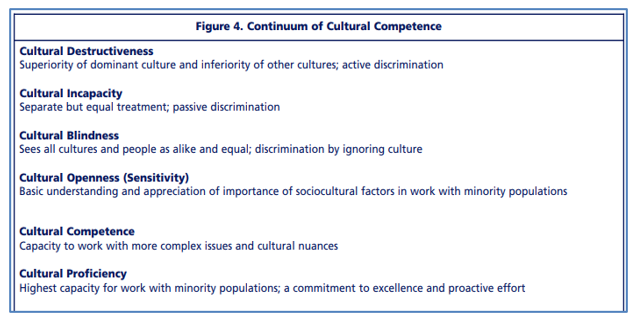

8. Culture and other contextual variables influence the supervision process; supervisors need to continually strive for cultural competence. Supervisors require cultural competence at several levels. Cultural competence involves the counselor’s response to clients, the supervisor’s response to counselors, and the pro gram’s response to the cultural needs of the diverse community it serves. Since supervisors are in a position to serve as catalysts for change, they need to develop proficiency in addressing the needs of diverse clients and personnel.

9. Successful implementation of EBPs requires ongoing supervision. Supervisors have a role in determining which specific EBPs are relevant for an organization’s clients (Lindbloom, Ten Eyck, & Gallon, 2005). Supervisors ensure that EBPs are successfully integrated into ongoing programmatic activities by training, encouraging, and monitoring counselors. Excellence in clinical supervision should provide greater adherence to the EBP model. Because State funding agencies now often require substance abuse treatment organizations to provide EBPs, supervision becomes even more important.

10. Supervisors have the responsibility to be gatekeepers for the profession. Supervisors are responsible for maintaining professional standards, recognizing and addressing impairment, and safeguarding the welfare of clients. More than anyone else in an agency, supervisors can observe counselor behavior and respond promptly to potential problems, including counseling some individuals out of the field because they are ill suited to the profession. This “gatekeeping” function is especially important for supervisors who act as field evaluators for practicum students prior to their entering the profession. Finally, supervisors also fulfill a gatekeeper role in performance evaluation and in providing formal recommendations to training institutions and credentialing bodies.

11. Clinical supervision should involve direct observation methods. Direct observation should be the standard in the field because it is one of the most effective ways of building skills, monitoring counselor performance, and ensuring quality care. Supervisors require training in methods of direct observation, and administrators need to provide resources for implementing direct observation. Although small substance abuse agencies might not have the resources for one way mirrors or videotaping equipment, other direct observation methods can be employed (see the section on methods of observation, pp. 20–24).

New LPC Supervisors

There are many challenges to be expected for LPC Supervisors, especially those without any prior supervisory experience. Many new LPC Supervisors have been clinical supervisors to employees in work settings before becoming LPC Supervisors to LPC Associates. The general supervisory experience attained prior to the role of LPC Supervisor may make the transition to supervising LPC Associates a little easier. However, the role of LPC Supervisor may bring on unique dynamics and duties that create a greater sense of uncertainty about your ability to be effective. You might feel that you knew what to do as a counselor, but feel totally lost with your new responsibilities as a supervisor.

Before you became a LPC Supervisor, you might have felt confidence in your clinical skills. Now you might feel unprepared and wonder if you need more training for your new role. Although you are a good counselor, you do not necessarily possess all the skills needed to be a good supervisor. Your new role requires a new body of knowledge and different skills, along with the ability to use your clinical skills in a different way. Be confident that you will acquire these skills over time.

Suggestions for LPC supervisors:

• Become very familiar with all the Rules and Statutes applicable to Texas LPCs and Associates found in various documents including the Texas Administrative Code and the Consolidated Rulebook for Professional Counseling found at the TSBEPC site.

• Become familiar with the Forms and Publications provided at the TSBEPC site including the forms under Supervised Experience Forms.

• Become familiar with the BHEC and TSEBPC sites and the information provided including: Board News; Meet the Board; Meeting Dates, Agendas, and Minutes; Statues and Rules; Jurisprudence Examination; Find A Supervisor; Fingerprint Information; FAQs; Human Trafficking Awareness, and other issues relevant to licensees.

• If your LPC Supervision of Associates is to occur through an employer, learn the employer’s policies and procedures and human resources procedures (e.g., hiring and firing, affirmative action requirements, format for conducting meetings, giving feedback, and making evaluations). Seek out this information as soon as possible through the human resources department or other resources within the organization.

• Take time to learn about your supervisees, their career goals, interests, developmental objectives, and perceived strengths.

• Establish a contractual relationship with supervisees, with clear goals and methods of supervision.

• Learn methods to help staff reduce stress, address competing priorities, resolve staff conflict, and other interpersonal issues in the workplace.

• Obtain 0n-going training in supervisory procedures and methods beyond the required 40 hour course required for Supervisory status.

• Find a mentor, either internal or external to the organization or private practice.

• Shadow a supervisor you respect who can help you learn the ropes of your new job.

• Ask Associates often, “How am I doing?” and “How can I improve my performance as a supervisor?”

• Seek supervision of your supervision from another LPC-Supervisor.

Problems and Resources

As a supervisor, you may encounter a broad array of issues and concerns, ranging from working within an employer’s system that does not fully support clinical supervision to working with resistant LPC Associates. Some of your supervisees may have been in the field longer than you have and see no need for supervision. Other counselors, having completed their graduate training, do not believe they need further supervision, especially not from a supervisor who might have less formal academic education or work experience than they have. A particularly important issue is when Associates believe their approach is the best one and are resistant to other models or techniques.

In addressing resistance, you must be clear regarding what your supervision program entails and must consistently communicate your goals and expectations to staff. To resolve defensiveness and engage your supervisees, you must also honor the resistance and acknowledge their concerns. Abandon trying to push the supervisee too far, too fast. Resistance is an expression of ambivalence about change and not a personality defect of the counselor. Instead of arguing with or exhorting supervisees, sympathize with their concerns, saying, “I understand this is difficult. How are we going to resolve these issues?”

When counselors respond defensively or reject directions from you, try to understand the origins of their defensiveness and to address their resistance. Self-disclosure by the supervisor about experiences as a supervisee, when appropriately used, may be helpful in dealing with defensive, anxious, fearful, or resistant staff. Work to establish a healthy, positive supervisory alliance with LPC Associates. Because many counselors have not been exposed to clinical supervision, it is important to clearly explain expectations and the rationale for those expectations, at the beginning of, and throughout, supervision. Discussing how differences of opinion or conflicts between supervisor and supervisee will be handled in advance is important.

Things Supervisors Should Know

There are several general truths that often apply to supervision. Some, if not all, of should be committed to memory:

1. The reason for supervision is to ensure quality client care. The primary goal of clinical supervision is to protect the welfare of the client and ensure the integrity of clinical services.

2. Supervision is all about the relationship. As in counseling, developing the alliance between the counselor and the supervisor is the key to good supervision.

3. Be human and have a sense of humor. As role models, you need to show that everyone makes mistakes and can admit to and learn from these mistakes.

4. Rely first on direct observation of your counselors and give specific feedback. The best way to determine a counselor’s skills is to observe him or her and to receive input from the clients about their perceptions of the counseling relationship.

5. Have and practice a model of counseling and of supervision; have a sense of purpose. Before you can teach a supervisee knowledge and skills, you must first know the philosophical and theoretical foundations on which you, as a supervisor, stand. Counselors need to know what they are going to learn from you, based on your model of counseling and supervision.

6. Make time to take care of yourself spiritually, emotionally, mentally, and physically. Again, as role models, counselors are watching your behavior. Do you “walk the talk” of selfcare?

7. As a supervisor, you have a wonderful opportunity to assist in the skill and professional development of Associates, advocating for the best interests of the supervisee, the client, and your organization.

Models of Clinical Supervision

It is important to work from a defined model of supervision and have a sense of purpose in your oversight role. Four supervisory orientations seem particularly relevant. They include:

• Competencybased models.

• Treatment based models.

• Developmental approaches.

• Integrated models.

Competency based models (e.g., microtraining, the Discrimination Model [Bernard & Goodyear, 2004], and the TaskOriented Model [Mead, 1990], focus primarily on the skills and learning needs of the supervisee and on setting goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely (SMART). They construct and implement strategies to accomplish these goals. The key strategies of competencybased models include applying social learning principles (e.g., modeling role reversal, role playing, and practice), using demonstrations, and using various supervisory functions (teaching, consulting, and counseling).

Treatmentbased supervision models train to a particular theoretical approach to counseling, incorporating EBPs into supervision and seeking fidelity and adaptation to the theoretical model. Motivational interviewing, cognitive–behavioral therapy, and psychodynamic psychotherapy are three examples. These models emphasize the counselor’s strengths, seek the supervisee’s understanding of the theory and model taught, and incorporate the approaches and techniques of the model. The majority of these models begin with articulating their treatment approach and describing their supervision model, based upon that approach.

Developmental models, such as Stoltenberg and Delworth (1987), understand that each counselor goes through different stages of development and recognize that movement through these stages is not always linear and can be affected by changes in assignment, setting, and population served.

Integrated models, including the Blended Model, begin with the style of leadership and articulate a model of treatment, incorporate descriptive dimensions of supervision, and address contextual and developmental dimensions into supervision. They address both skill and competency development and affective issues, based on the unique needs of the supervisee and supervisor. Finally, integrated models seek to incorporate EBPs into counseling and supervision.

It is important to identify your model of counseling and your beliefs about change, and to articulate a workable approach to supervision that fits the model of counseling you use. Theories are conceptual frame works that enable you to make sense of and organize your counseling and supervision and to focus on the most salient aspects of a counselor’s practice. You may find some of the questions below to be relevant to both supervision and counseling. The answers to these questions influence both how you supervise and how the counselors you supervise work:

• What are your beliefs about how people change in both treatment and clinical supervision?

• What factors are important in treatment and clinical supervision?

• What universal principles apply in supervision and counseling and which are unique to clinical supervision?

• What conceptual frameworks of counseling do you use (for instance, cognitive–behavioral therapy, 12Step facilitation, psychodynamic, behavioral)?

• What are the key variables that affect outcomes? (Campbell, 2000)

According to Bernard and Goodyear (2004) and Powell and Brodsky (2004),the qualities of a good model of clinical supervision are:

• Rooted in the individual, beginning with the supervisor’s self, style, and approach to leadership.

• Precise, clear, and consistent.

• Comprehensive, using current scientific and evidencebased practices.

• Operational and practical, providing specific concepts and practices in clear, useful, and measurable terms.

• Outcomeoriented to improve counselor competence; make work manageable; create a sense of mastery and growth for the counselor; and address the needs of the organization, the supervisor, the supervisee, and the client.

Finally, it is imperative to recognize that, whatever model you adopt, it needs to be rooted in the learning and developmental needs of the supervisee, the specific needs of the clients they serve, the goals of the agency in which you work, and in the ethical and legal boundaries of practice. These four variables define the context in which effective supervision can take place.

Developmental Stages of Counselors

Counselors are at different stages of professional development. Thus, regardless of the model of supervision you choose, you must take into account the supervisee’s level of training, experience, and proficiency. Different supervisory approaches are appropriate for counselors at different stages of development. An understanding of the supervisee’s (and supervisor’s) developmental needs is an essential ingredient for any model of supervision.

Various paradigms or classifications of developmental stages of clinicians have been developed. This course specifically examines the Integrated Developmental Model (IDM) of Stoltenberg, McNeill, and Delworth (1998). This schema uses a threestage approach. The three stages of development have different characteristics and appropriate supervisory methods.

Further application of the IDM to the substance abuse field is needed. (For additional information, see Anderson, 2001.)

It is important to keep in mind several general cautions and principles about counselor development, including:

• There is a beginning but not an end point for learning clinical skills; be careful of counselors who think they “know it all.”

• Take into account the individual learning styles and personalities of your supervisees and fit the supervisory approach to the developmental stage of each counselor.

• There is a logical sequence to development, although it is not always predictable or rigid; some counselors may have been in the field for years but remain at an early stage of professional development, whereas others may progress quickly through the stages.

• Counselors at an advanced developmental level have different learning needs and require different supervisory approaches from those at Level 1; and

• The developmental level can be applied for different aspects of a counselor’s overall competence (e.g., Level 2 mastery for individual counseling and Level 1 for couples counseling).

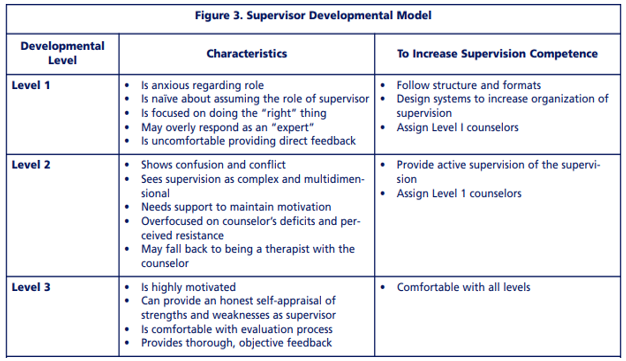

Developmental Stages of Supervisors

Just as counselors go through stages of development, so do supervisors. The developmental model presented in figure 3 provides a framework to explain why supervisors act as they do, depending on their developmental stage. It would be expected that someone new to supervision would be at a Level 1 as a supervisor. However, supervisors should be at least at the second or third stage of counselor development. If a newly appointed supervisor is still at Level 1 as a counselor, he or she may have little to offer to more seasoned supervisees.

Cultural and Contextual Factors

Culture is one of the major contextual factors that influence supervisory interactions. Other contextual variables include race, ethnicity, age, gender, discipline, academic background, religious and spiritual practices, disability, and recovery versus nonrecovery status. The relevant variables in the supervisory relationship occur in the context of the supervisor, supervisee, client, and the setting in which supervision occurs. More care should be taken to:

• Identify the competencies necessary for counselors to work with diverse individuals and navigate intercultural communities.

• Identify methods for supervisors to assist counselors in developing these competencies.

• Provide evaluation criteria for supervisors to determine whether their supervisees have met minimal competency standards for effective and relevant practice.

Models of supervision have been strongly influenced by contextual variables and their influence on the supervisory relationship and process, such as Holloway’s Systems Model (1995) and Constantine’s Multicultural Model (2003).

The competencies listed in SAMHSA’s TAP 21A publication reflect the importance of culture in supervision (CSAT, 2007). Supervisors are encouraged to conduct self examination of attitudes toward culture and other contextual variables.

Cultural competence “refers to the ability to honor and respect the beliefs, language, interpersonal styles, and behaviors of individuals and families receiving services, as well as staff who are providing such services. Cultural competence is a dynamic, ongoing, developmental process that requires a commitment and is achieved over time” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2003, p. 12). Culture shapes belief systems, particularly concerning issues related to mental health and substance abuse, as well as the manifestation of symptoms, relational styles, and coping patterns.

There are three levels of cultural consideration for the supervisory process: the issue of the culture of the client being served and the culture of the counselor in supervision. Holloway (1995) emphasizes the cultural issues of the agency, the geographic environment of the organization, and many other contextual factors. Specifically, there are three important areas in which cultural and contextual factors play a key role in supervision: in building the supervisory relationship or working alliance, in addressing the specific needs of the client, and in building supervisee competence and ability. It is your responsibility to address your supervisees’ beliefs, attitudes, and biases about cultural and contextual variables to advance their professional development and promote quality client care.

Becoming culturally competent and able to integrate other contextual variables into supervision is a complex, long term process. Although you may never have had specialized training in multicultural counseling, some of your supervisees may have (see Constantine, 2003). Regardless, it is your responsibility to help supervisees build on the cultural competence skills they possess as well as to focus on their cultural competence deficits. It is important to initiate discussion of issues of culture, race, gender, sexual orientation, and the like in supervision to model the kinds of discussion you would like counselors to have with their clients. If these issues are not addressed in supervision, counselors may come to believe that it is inappropriate to discuss them with clients and have no idea how such dialog might proceed. These discussions prevent mis understandings with supervisees based on cultural or other factors. Another benefit from these discussions is that counselors will eventually achieve some level of comfort in talking about culture, race, ethnicity, and diversity issues.

If you haven’t done it as a counselor, early in your tenure as a supervisor you will want to examine your culturally influenced values, attitudes, experiences, and practices and to consider what effects they have on your dealings with supervisees and clients.

Counselors should undergo a similar review as preparation for when they have clients of a culture different from their own. Some questions to keep in mind are:

• What did you think when you saw the supervisee’s last name?

• What did you think when the supervisee said his or her culture is X, when yours is Y?

• How did you feel about this difference?

• What did you do in response to this difference?

Constantine (2003) suggests that supervisors can use the following questions with supervisees:

• What demographic variables do you use to identify yourself?

• What worldviews (e.g., values, assumptions, and biases) do you bring to supervision based on your cultural identities?

• What struggles and challenges have you faced working with clients who were from different cultures than your own?

Beyond self-examination, supervisor will want continuing education classes, workshops, and conferences that address cultural competence and other contextual factors. Community resources, such as community leaders, ministers, elders, and healers can contribute to your understanding of the culture your organization serves. Finally, supervisors (and counselors) should participate in multicultural activities, such as com munity events, discussion groups, religious festivals, and other ceremonies.

The supervisory relationship includes an inherent power differential, and it is important to pay attention to this disparity, particularly when the supervisee and the supervisor are from different cultural groups. A potential for the misuse of that power exists at all times but especially when working with supervisees and clients within multicultural contexts. When the supervisee is from a minority population and the supervisor is from a majority population, the differential can be exaggerated. You will want to prevent institutional discrimination from affecting the quality of supervision.

Ethical and Legal Issues

The supervisor is responsible for ethical and legal issues involving the Associate. First, you are responsible for upholding the highest standards of ethical, legal, and moral practices and for serving as a model of practice to supervisees. Further, you should be aware of and respond to ethical concerns. Part of your job is to help integrate solutions to everyday legal and ethical issues into clinical practice.

Some of the underlying assumptions of incorporating ethical issues into clinical supervision include:

• Ethical decision-making is a continuous, active process.

• Ethical standards are not a cookbook. They tell you what to do, not always how.

• Each situation is unique. Therefore, it is imperative that all personnel learn how to “think ethically” and how to make sound legal and ethical decisions.

• The most complex ethical issues arise in the context of two ethical behaviors that conflict; for instance, when a counselor wants to respect the privacy and confidentiality of a client, but it is in the client’s best interest for the counselor to contact someone else about his or her care.

• Therapy is conducted by fallible beings; people make mistakes—hopefully, minor ones.

• Sometimes the answers to ethical and legal questions are elusive. Ask a dozen people, and you’ll likely get twelve different points of view.

Supervisees should acquire resources on legal and ethical issues. Legal and ethical issues that are critical to clinical supervisors are many, but include (1) vicarious liability, (2) dual relationships and boundary concerns, (4) informed consent, (5) confidentiality, and (6) supervisor ethics.

Direct Versus Vicarious Liability

An important distinction needs to be made between direct and vicarious liability. Direct liability of the supervisor might include dereliction of supervisory responsibility, such as “not making a reasonable effort to supervise.”

In vicarious liability, a supervisor can be held liable for damages incurred as a result of negligence in the supervision process. Examples of negligence include providing inappropriate advice to a counselor about a client (for instance, discouraging a counselor from conducting a suicide screen on a depressed client), failure to listen carefully to a supervisee’s comments about a client, and the assignment of clinical tasks to inadequately trained counselors. The key legal question is: “Did the supervisor conduct herself in a way that would be reasonable for someone in her position?” or “Did the supervisor make a reasonable effort to supervise?” A generally accepted time standard for a “reasonable effort to supervise” in the behavioral health field is 1 hour of supervision for every 20–40 hours of clinical services. Of course, other variables (such as the quality and content of clinical supervision sessions) also play a role in a rea sonable effort to supervise.

Supervisory vulnerability increases when the counselor has been assigned too many clients, when there is no direct observation of a counselor’s clinical work, when staff are inexperienced or poorly trained for assigned tasks, and when a supervisor is not involved or not available to aid the clinical staff. In legal texts, vicarious liability is referred to as “respondeat superior.”

Dual Relationships and Boundary Issues

Dual relationships can occur at two levels: between supervisors and Associates and between Associates and clients. You have a mandate to maintain boundaries with the Associates you supervise, and help your supervisees recognize and manage boundary issues with clients. A dual relationship occurs in supervision when a supervisor has a primary professional role with a supervisee and, at an earlier time, simultaneously or later, engages in another relationship with the supervisee that transcends the professional relationship.

Examples of dual relationships in supervision include providing therapy for a current or former supervisee, developing an emotional relationship with a supervisee or former supervisee, or becoming sexually involved with a current Associate or within five years after supervision has terminated. Even after five years of cessation of supervision, the Supervisor must make sure the conduct is consensual, not the result of sexual exploitation, and not detrimental to the client. The licensee must demonstrate there has been no exploitation in light of all relevant factors, including, but not limited to:

(A) the amount of time that has passed since therapy terminated;

(B) the nature and duration of the therapy;

(C) the circumstances of termination;

(D) the client's, LPC Associate's, or student's personal history;

(E) the client's, LPC Associate's, or student's current mental status;

(F) the likelihood of adverse impact on the client, LPC Associate, or student and others; and

(G) any statements or actions made by the licensee during the course of therapy, supervision, or educational services suggesting or inviting the possibility of a post-termination sexual or romantic relationship with the client, LPC Associate, or student. There are many other Rules in the TAC applicable to sexual contact between supervisors and Associates. Supervisors should carefully consider and commit to upholding all of the Rules in the TAC before contemplating such contact with any Associate regardless of how much time has elapsed after supervision has ended. Also, keep in mind that According to Rule 681.93, LPC Supervisors; “must avoid any relationship that impairs the supervisor’s objective, professional judgment.”

Obviously, there are varying degrees of harm or potential harm that might occur as a result of dual relationships, and some negative effects of dual relationships might not be apparent until later.

You have the responsibility of weighing with the counselor the anticipated and unanticipated effects of dual relationships, helping the supervisee’s self-reflective awareness when boundaries become blurred, when he or she is getting close to a dual relationship, or when he or she is crossing the line in the clinical relationship.

Exploring dual relationship issues with counselors in clinical supervision can raise its own professional dilemmas. For instance, clinical supervision involves unequal status, power, and expertise between a supervisor and supervisee. Being the evaluator of a counselor’s performance and gatekeeper for training programs or credentialing bodies also might involve a dual relationship. Further, supervision can have therapylike qualities as you explore countertransference issues with supervisees, and there is an expectation of professional growth and self-exploration. What makes a dual relationship unethical in supervision is the abusive use of power by either party, the likelihood that the relationship will impair or injure the supervisor’s or supervisee’s judgment, and the risk of exploitation.

One of the most common basis for legal action against counselors and the most frequently heard complaint by certification boards against counselors is some form of boundary violation or sexual impropriety.

Codes of ethics for most professions clearly advise that dual relationships between counselors and clients should be avoided. This topic must be stressed with Associates. Some, but not all, of the relevant Texas Administrative Code come from Rule 681.41:

►A licensee must not engage in activities for the licensee's personal gain at the expense of a client.

►A licensee must set and maintain professional boundaries.

►Except as provided by this subchapter, non-therapeutic relationships with clients are prohibited.

• A non-therapeutic relationship is any non-counseling activity initiated by either the licensee or client that results in a relationship unrelated to therapy.

• A licensee may not engage in a non-therapeutic relationship with a client if the relationship begins less than two (2) years after the end of the counseling relationship; the non-therapeutic relationship must be consensual, not the result of exploitation by the licensee, and is not detrimental to the client.

• A licensee may not engage in sexual contact with a client if the contact begins less than five (5) years after the end of the counseling relationship; the non-therapeutic relationship must be consensual, not the result of exploitation by the licensee, and is not detrimental to the client.

Dual relationships between counselors and supervisors are also a concern and are addressed in the counselors’ codes and those of other professions as well. Problematic dual relationships between supervisees and supervisors might include intimate relationships (sexual and nonsexual) and therapeutic relationships, wherein the supervisor becomes the counselor’s therapist. Sexual involvement, referred to as sexual contact, sexual exploitation and therapeutic deception in the TAC, between the supervisor and supervisee can include sexual attraction, harassment, consensual (but hidden) sexual relationships, or intimate romantic relationships. Other common boundary issues include asking the supervisee to do favors, providing preferential treatment, socializing outside the work setting, and using emotional abuse to enforce power.

It is imperative that all parties understand what constitutes a dual relationship between supervisor and supervisee and avoid these dual relationships. Sexual relationships between supervisors and supervisees and counselors and clients occur far more frequently than one might realize (Falvey, 2002b). In many States, they constitute a legal transgression as well as an ethical violation.

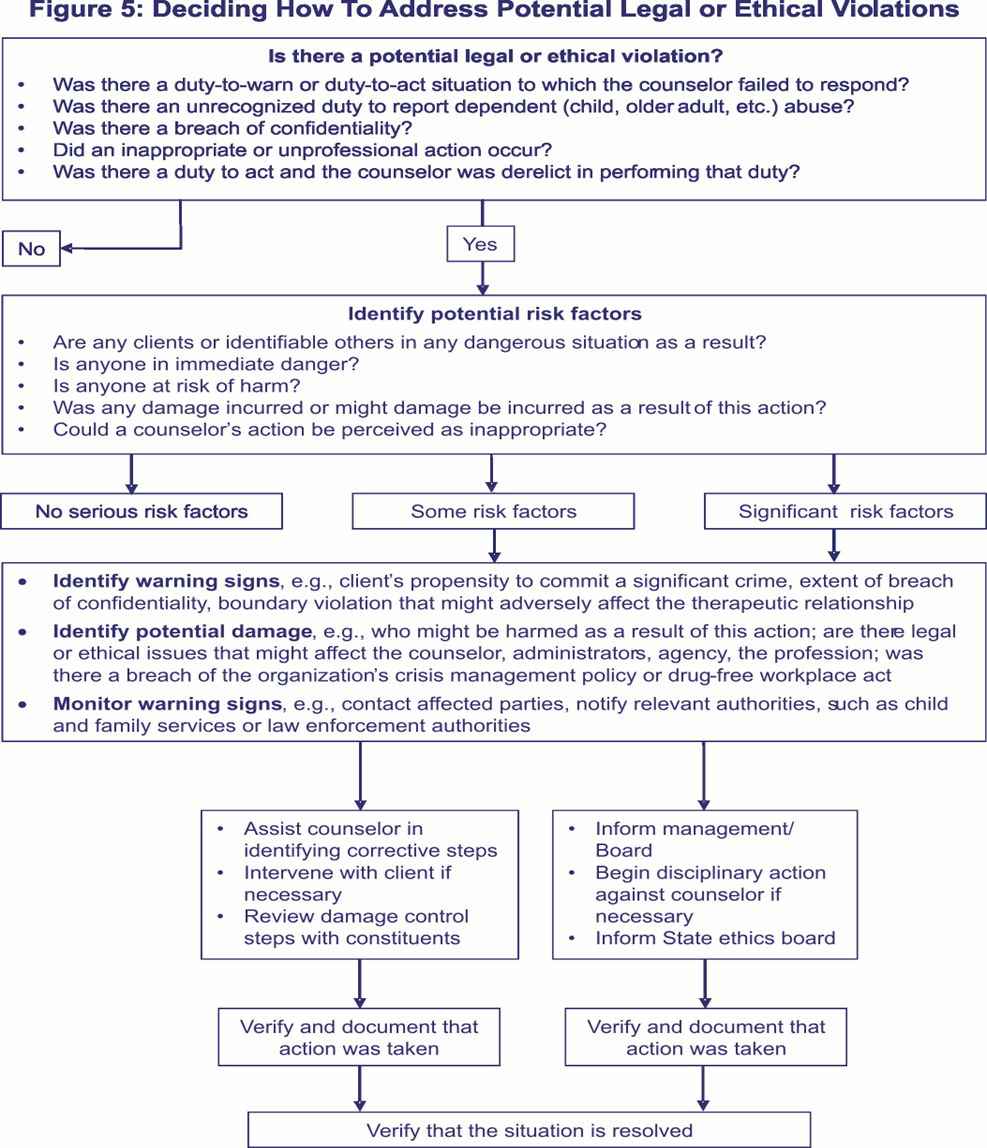

The decision tree presented in figure 5 indicates how a supervisor might manage a situation where he or she is concerned about a possible ethical or legal violation by a counselor.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is key to protecting the counselor and/or supervisor from legal concerns, requiring the recipient of any service or intervention to be sufficiently aware of what is to happen, and of the potential risks and alternative approaches, so that the person can make an informed and intelligent decision about participating in that service. The supervisor must inform the supervisee about the process of supervision, the feedback and evaluation criteria, and other expectations of supervision. The supervision contract should clearly spell out these issues.

Supervisors must ensure that the supervisee has informed the client about the parameters of counseling and supervision (such as the use of live observation, video or audiotaping).

Confidentiality

In supervision, regardless of whether there is a written or verbal contract between the supervisor and supervisee, there is an implied contract and duty of care because of the supervisor’s vicarious liability. Informed consent and concerns for confidentiality should occur at three levels: client consent to treatment, client consent to supervision of the case, and supervisee consent to supervision (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004). In addition, there is an implied consent and commitment to confidentiality by supervisors to assume their supervisory responsibilities and institutional consent to comply with legal and ethical parameters of supervision.

With informed consent and confidentiality comes a duty not to disclose certain relational communication. Limits of confidentiality of supervision session content should be stated in all organizational contracts with training institutions and credentialing bodies.

Criteria for waiving client and supervisee privilege should be stated in institutional policies and discipline-specific codes of ethics and clarified by advice of legal counsel and the courts. Because standards of confidentiality are determined by State legal and legislative systems, it is prudent for supervisors to consult with an attorney to determine the State codes of confidentiality and clinical privileging.

Supervisors need to train counselors in confidentiality regulations and to adequately document their supervision, including discussions and directives, and inform clients of the limits of confidentiality as part of the agency’s informed consent procedures.

Organizations should have a policy stating how clinical crises will be handled. What mechanisms are in place for responding to crises? In what timeframe will a supervisor be notified of a crisis situation? Supervisors must document all discussions with counselors concerning crises and limits on confidentiality.

New technology brings new confidentiality concerns. Websites now dispense information about substance abuse treatment and provide counseling services.

With the growth in online counseling and supervision, the following concerns emerge: (a) how

to maintain confidentiality of information, (b) how to ensure the competence and qualifications of counselors pro viding online services, and (c) how to establish reporting requirements and duty to warn when services are conducted across State and international boundaries. New standards will need to be written to address these issues.

Supervisor Ethics

In general, supervisors adhere to the same standards and ethics as counselors with regard to dual relationship and other boundary violations.

Supervisors will:

• Uphold the highest professional standards of the field.

• Seek professional help (outside the work setting) when personal issues interfere with their clinical and/or supervisory functioning.

• Conduct themselves in a manner that models and sets an example for agency mission, vision, philosophy, wellness, recovery, and consumer satisfaction.

• Reinforce zero tolerance for interactions that are not professional, courteous, and compassionate.

• Treat supervisees, colleagues, peers, and clients with dignity, respect, and honesty.

• Adhere to the standards and regulations of confidentiality as dictated by the field. This applies to the supervisory as well as the counseling relationship.

Monitoring Performance

The goal of supervision is to ensure quality care for the client, which entails monitoring the clinical performance of staff. Your first step is to educate supervisees in what to expect from clinical supervision.

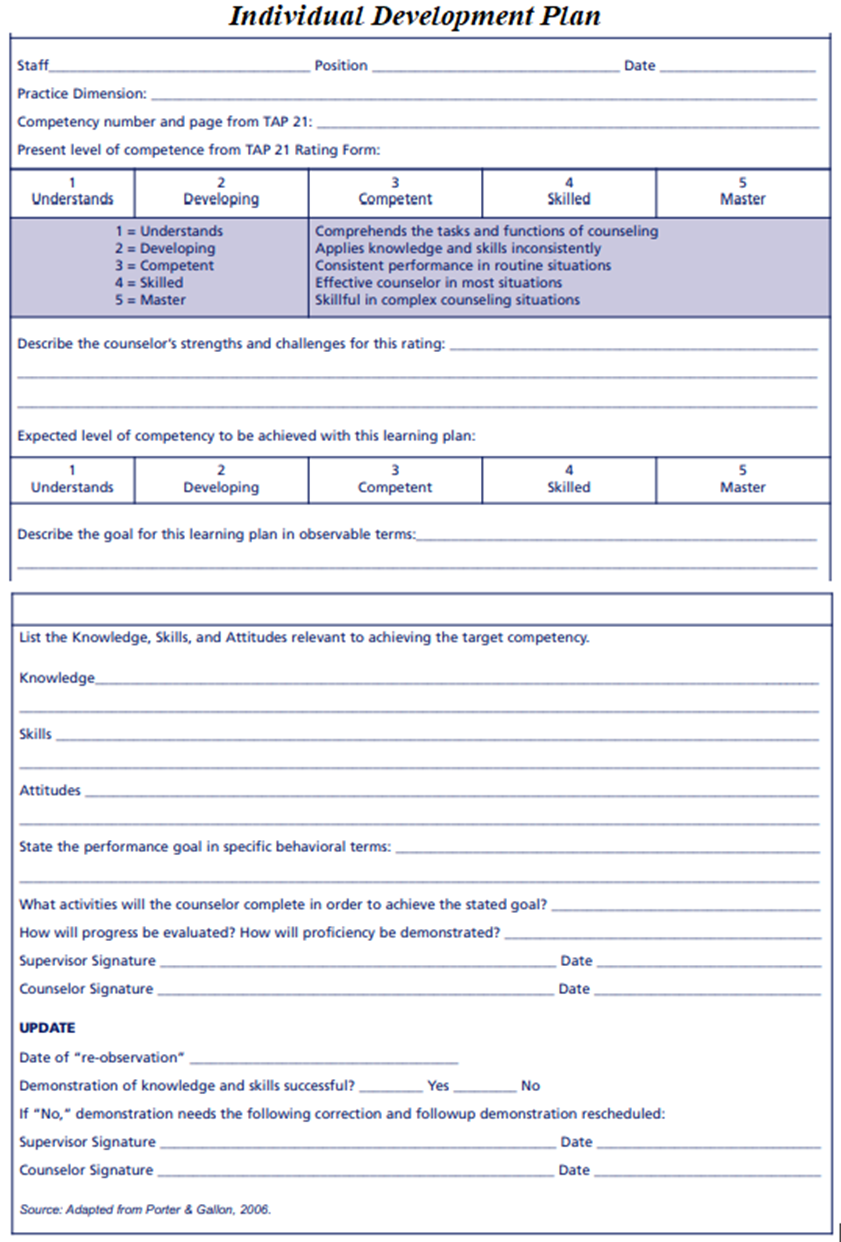

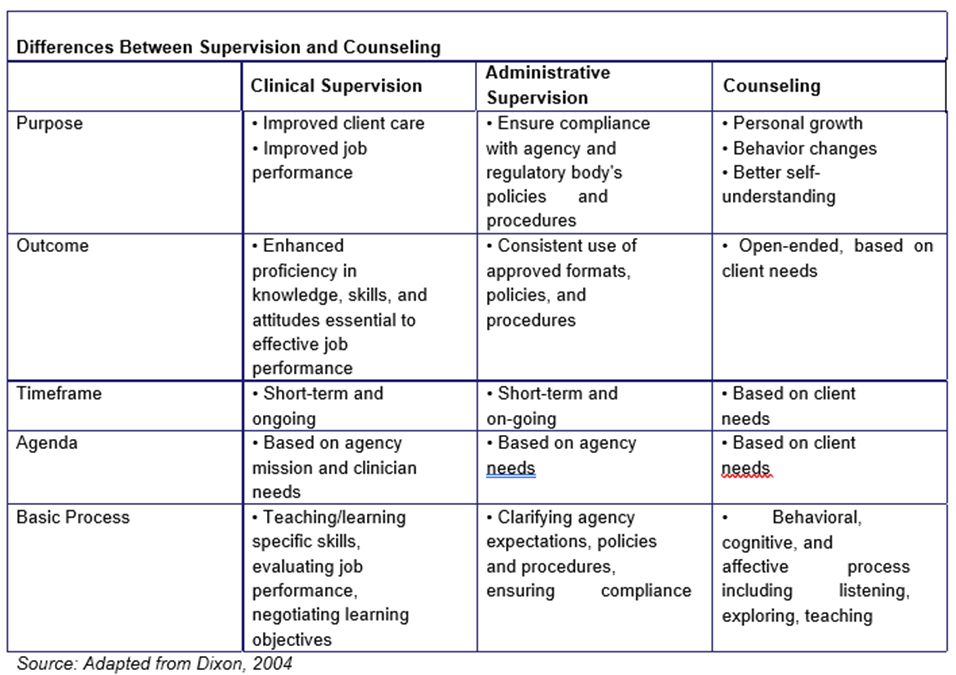

Once the functions of supervision are clear, you should regularly evaluate the counselor’s progress in meeting organizational and clinical goals as set forth in an Individual Development Plan (IDP) (see the section on IDPs below). As clients have an individual treatment plan, counselors also need a plan to promote skill development.

Behavioral Contracting in Supervision

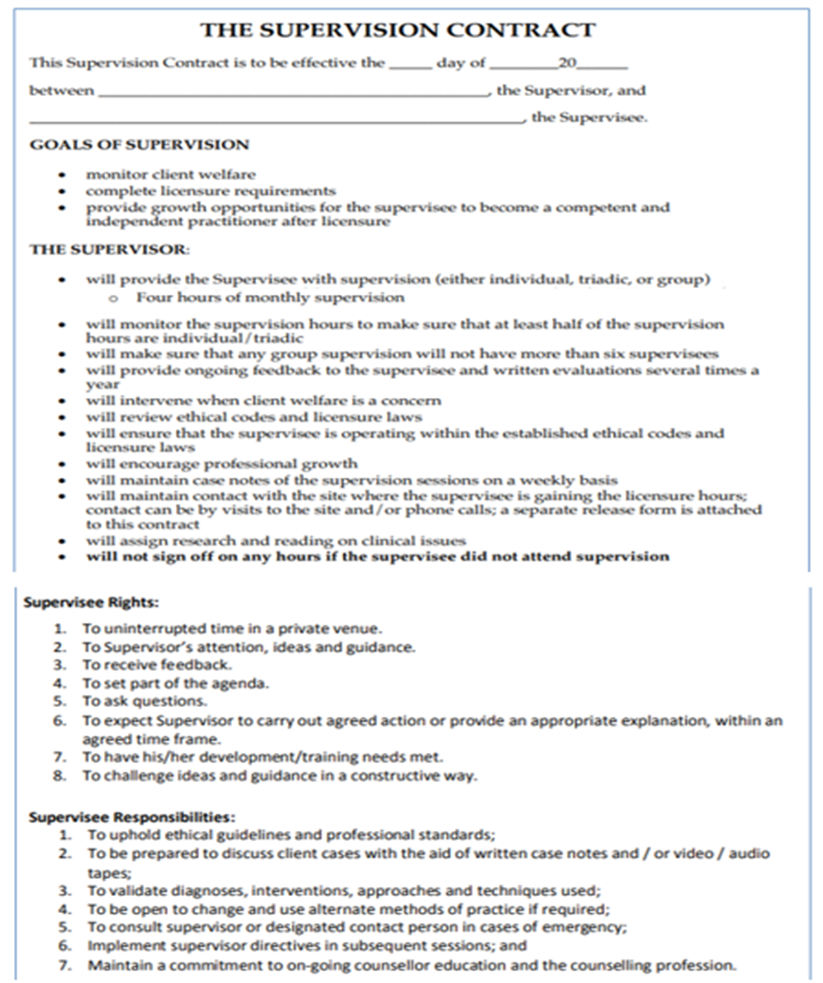

Among the first tasks in supervision is to establish a contract for supervision that outlines realistic accountability for both yourself and your supervisee. The contract should be in writing and should include the purpose, goals, and objectives of supervision; the context in which supervision is provided; ethical and institutional policies that guide supervision and clinical practices; the criteria and methods of evaluation and outcome measures; the duties and responsibilities of the supervisor and supervisee; procedural considerations (including the format for taping and opportunities for live observation); and the supervisee’s scope of practice and competence. The contract for supervision should state the length of supervision sessions, and sanctions for noncompliance by either the supervisee or supervisor. The agreement should be compatible with the developmental needs of the supervisee and address the obstacles to progress (lack of time, performance anxiety, resource limitations). An example of a contract that incorporates areas to consider:

Once a behavioral contract has been established, the next step is to develop an IDP.

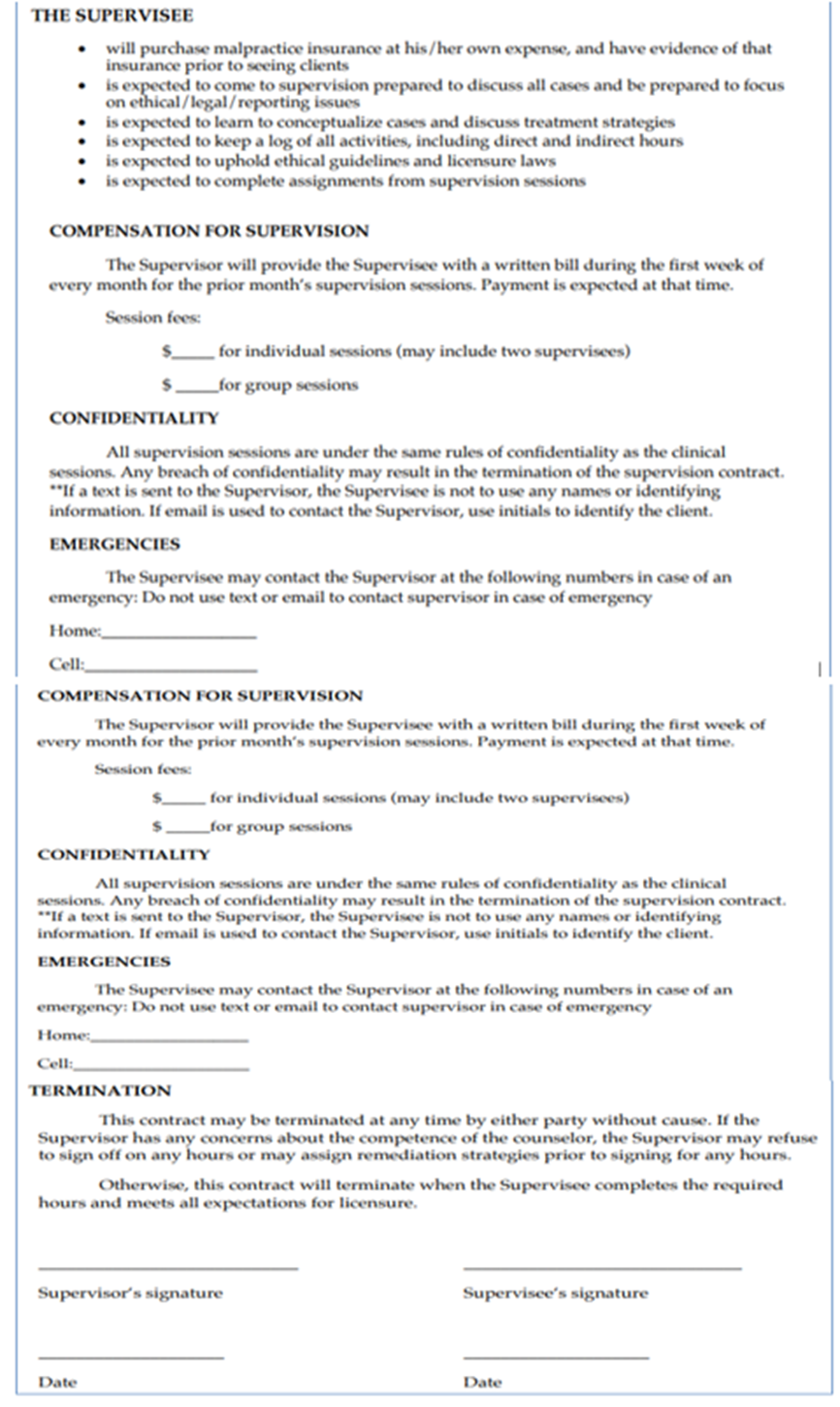

Individual Development Plan

The IDP is a detailed plan for supervision that includes the goals that you and the Associate wish to address over a certain time period. Each of you should sign and keep a copy of the IDP for your records. The goals are normally stated in terms of skills the counselor wishes to build or professional resources the counselor wishes to develop. These skills and resources are generally oriented to the counselor’s job in the program or activities that would help the counselor develop professionally. The IDP should specify the timelines for change, the observation methods that will be employed, expectations for the supervisee and the supervisor, the evaluation procedures that will be employed, and the activities that will be expected to improve knowledge and skills.

As a supervisor, you should have your own IDP, based on the supervisory competencies that addresses your training goals. This IDP can be developed in cooperation with your supervisor, or in external supervision, peer input, academic advisement, or mentorship.

Evaluation of LPC Associates

Supervision inherently involves evaluation, building on a collaborative relationship between you and the Associate. Evaluation may not be easy for some supervisors. Although everyone wants to know how they are doing, counselors are not always comfortable asking for feedback. And, as most supervisors prefer to be liked, you may have difficulty giving clear, concise, and accurate evaluations to staff.

The two types of evaluation are formative and summative. A formative evaluation is an ongoing status report of the counselor’s skill development, exploring the questions “Are we addressing the skills or competencies you want to focus on?” and “How do we assess your current knowledge and skills and areas for growth and development?”

Summative evaluation is a more formal rating of the counselor’s overall performance, fitness for the full licensure, and job rating. It answers the question, “How does the counselor measure up?” Typically, summative evaluations are done annually and focus on the counselor’s overall strengths, limitations, and areas for future improvement.

It should be acknowledged that supervision is inherently an unequal relationship. In most cases, the supervisor has positional power over the counselor. Therefore, it is important to establish clarity of purpose and a positive context for evaluation. Procedures should be spelled out in advance, and the evaluation process should be mutual, flexible, and continuous.

The evaluation process inevitably brings up supervisee anxiety and defensiveness that need to be addressed openly. It is also important to note that each individual counselor will react differently to feedback; some will be more open to the process than others.

There has been considerable research on supervisory evaluation, with these findings:

• The supervisee’s confidence and efficacy are correlated with the quality and quantity of feedback the supervisor gives to the supervisee (Bernard & Goodyear, 2004).

• Ratings of skills are highly variable between supervisors, and often the supervisor’s and supervisee’s ratings differ or conflict (Eby, 2007).

• Good feedback is provided frequently, clearly, and consistently and is SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely) (Powell & Brodsky, 2004).

Direct observation of the counselor’s work is the desired form of input for the supervisor. Although direct observation is not always possible, ethical and legal considerations and evidence support that direct observation as preferable. One of the least desirable feedback is unannounced observation by supervisors followed by vague, perfunctory, indirect, or hurtful delivery.

Clients are often the best assessors of the skills of the counselor. Supervisors should routinely seek input from the clients as to the outcome of treatment. The method of seeking input should be discussed in the initial supervisory sessions and be part of the supervision contract. In an inpatient setting, you might regularly meet with clients after sessions to discuss how they are doing, how effective the counseling is, and the quality of the therapeutic alliance with the counselor.

Before formative evaluations begin, methods of evaluating performance should be discussed, clarified in the initial sessions, and included in the initial contract so that there will be no surprises. Formative evaluations should focus on changeable behavior and, whenever possible, be separate from the overall annual performance appraisal process. To determine the counselor’s skill development, you should use written competency tools, direct observation, counselor self-assessments, client evaluations, work samples (files and charts), and peer assessments. It is important to acknowledge that counselor evaluation is essentially a subjective process involving supervisors’ opinions of the counselors’ competence.

Addressing Burnout and Compassion Fatigue

Did you ever hear a counselor say, “I came into counseling for the right reasons. At first I loved seeing clients. But the longer I stay in the field, the harder it is to care. The joy seems to have gone out of my job. Should I get out of counseling as many of my colleagues are doing?” Most counselors come into the field with a strong sense of calling and the desire to be of service to others, with a strong pull to use their gifts and make themselves instruments of service and healing. The counseling field risks losing many skilled and compassionate licensees when the life goes out of their work. Some counselors simply withdraw, care less, or get out of the field entirely. Many just complain or suffer in silence. Given the caring and dedication that brings counselors into the field, it is important for you to help them address their questions and doubts.

You can help counselors with selfcare; help them look within; become resilient again; and rediscover what gives them joy, meaning, and hope in their work. Counselors need time for reflection, to listen again deeply and authentically. You can help them redevelop their innate capacity for compassion, to be an openhearted presence for others.

You can help counselors develop a life that does not revolve around work. This has to be supported by the organization’s culture and policies that allow for appropriate use of time off and selfcare without punishment. Aid them by encouraging them to take earned leave and to take “mental health” days when they are feeling tired and burned out. Remind staff to spend time with family and friends, exercise, relax, read, or pursue other lifegiving interests.

It is important for the clinical supervisor to normalize the counselor’s reactions to stress and compassion fatigue in the workplace as a natural part of being an empathic and compassionate person and not an individual failing or pathology. (See Burke, Carruth, & Prichard, 2006.)

Rest is good; selfcare is important. Everyone needs times of relaxation and recreation. Often, a month after a refreshing vacation you lose whatever gain you made. Instead, longer term gain comes from finding what brings you peace and joy. It is not enough for you to help counselors understand “how” to coun sel, you can also help them with the “why.” Why are they in this field? What gives them meaning and pur pose at work? When all is said and done, when coun selors have seen their last client, how do they want to be remembered? What do they want said about them as counselors? Usually, counselors’ responses to this question are fairly simple: “I want to be thought of as a caring, compassionate person, a skilled helper.” These are important spiritual questions that you can discuss with your supervisees.

Other suggestions include:

• Help staff identify what is happening within their organization or place of employment that might be contributing to their stress and learn how to address the situation in a way that is productive to the client, the counselor, and the organization.

• Get training in identifying the signs of primary stress reactions, secondary trauma, compassion fatigue, vicarious traumatization, and burnout. Help staff match up selfcare tools to specifically address each of these experiences.

• Support staff in advocating for organizational change when appropriate and feasible as part of your role as liaison between administration and clinical staff.

• Assist staff in adopting lifestyle changes to increase their emotional resilience by reconnecting to their world (family, friends, sponsors, mentors), spending time alone for selfreflection, and forming habits that reenergize them.

• Help them eliminate the “what ifs” and negative selftalk. Help them let go of their idealism that they can save the world.

• If possible in the current work environment, set parameters on their work by helping them adhere to scheduled time off, keep lunch time personal, set reasonable deadlines for work completion, and keep work away from personal time.

• Teach and support generally positive work habits. Some counselors lack basic organizational, team work, phone, and time management skills (ending sessions on time and scheduling to allow for docu mentation). The development of these skills helps to reduce the daily wear that erodes wellbeing and contributes to burnout.

• Ask them “When was the last time you had fun?” “When was the last time you felt fully alive?” Suggest they write a list of things about their job about which they are grateful. List five people they care about and love. List five accomplish ments in their professional life. Ask “Where do you want to be in your professional life in 5 years?”

You have a fiduciary responsibility given you by clients to ensure counselors are healthy and whole. It is your responsibility to aid counselors in addressing their fatigue and burnout.

Gatekeeping Functions