Ethics for Texas Licensed Professional Counselors (6 hours)

NOTICE: BE SURE TO CLICK THE ARROW AT THE END OF THE TEXT TO RECEIVE CREDIT FOR PART ONE. AFTER YOU COMPLETE PART ONE (TEXT) AND PART TWO (QUIZ) YOU CAN PRINT YOUR CERTIFICATE.

Updates were made to this course on November 20, 2025.

Information about this course:

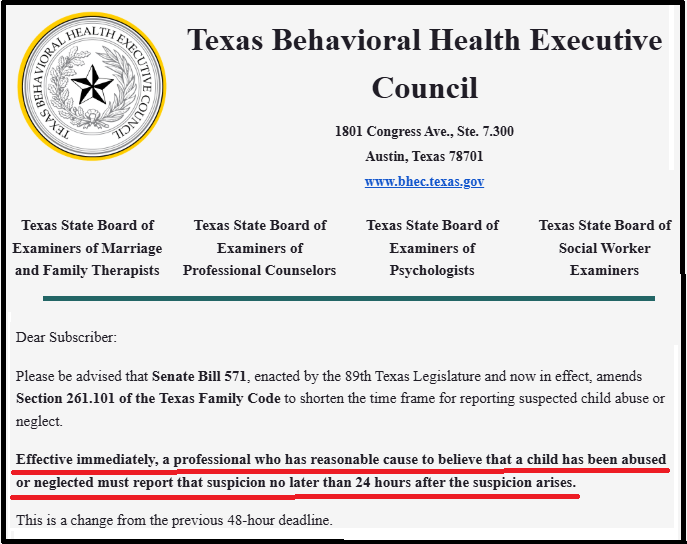

There are often important changes to rules that govern Texas LPCs. The Texas Behavioral Health Executive Council/Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors site has a new look that licensees may want to become familiar. We try to make this course as current as possible, but please take the initiative to stay current regarding on-going changes where both adopted changes, as well as proposed changes, to the Texas Administrative Code are listed.

This is an online course for Texas LPCs that allows participants to print their certificates immediately after completion of the online quiz at the end of the course. This six-hour ethics course is a review of the “Consolidated Rulebook for Professional Counseling” published by the Texas Behavioral Health Executive Council and Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors. This Rule booklet lists the Texas Administrative Code rules applicable to Texas LPCs and is updated frequently to reflect changes in legislative statutes. In 2025, Rulebooks were published in March, July, and November.

The Purpose of This Course:

The purpose of this course is to help Texas LPCs review ethical standards pertinent to the practice of counseling. The course will focus specifically on the statutes and rules codified in the Texas Administrative Code relevant to Texas LPCs and published in the Consolidated Rulebook for Professional Counseling.

Learning Objectives:

Participants will:

1. Identify regulated activities of Texas LPCs found in the Texas Administrative Code, Chapter 681, Subchapter B (Rules of Practice).

2. Identify the authorized counseling methods, techniques and modalities listed in Section 681.31 and the process for determining a licensee’s competence to use a specific approach.

3. Review the different rules identified in Sections 681.35 through 681.38 as they pertain to informed consent, client records, billing and financial arrangements, and conflicts, boundaries, dual relationships, and termination of relationships.

4. Summarize the definition and actions that constitute general ethical requirements in Rule 681.41 and sexual misconduct in Rule 681.42.

5. Identify rules regarding testing, drug and alcohol use, confidentiality and required reporting.

6. Describe rules related to licensees and the council, assumed names, advertising and announcements, research and publications found in Rules 681.46 through 681.50.

Before starting this course, we recommend you review the continuing education requirements for Texas LPCs found at the TSBEPC website.

ETHICS FOR TEXAS LICENSED PROFESSIONAL COUNSELORS (6 HOURS)

Note: One of the best resources for Texas LPCs to stay up-to-date with ethical standards is through the website of the BHEC and Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors. Many links directly and indirectly related to ethics are found at the site with the option of email notification of updates being sent to licensees.

The Consolidated Rulebook for Professional Counseling was last published by the BHEC on November 14th, 2025. This booklet is published as a courtesy to the public. The website cautions: "You are cautioned against relying solely upon these rulebooks and urged to review the current rules which are available through the links below. Moreover, if a conflict exists between a rulebook and the rules published on the Secretary of State’s website, the version on the Secretary of State’s website shall control. Compliance with the law cannot be excused due to an outdated, mistaken, or erroneous reference in a rulebook."

Keep in mind that, although the latest Rules (published November 14th, 2025) regarding the content of this ethics course (Subchapter B: Rules of Practice) were unchanged since the last Rulebook was published in July, one of the recent key changes not in the "Rules of Practice" section was Rule 681.140 "Requirements for Continuing Education" that went into effect July 20,2025. This change impacts the kinds of courses licensees can take to fulfill continuing education requirements stated in 681.140 (a)(1). The course offered at this site (LPCrenewal.com) was changed from "Improving Cultural Competence for Texas LPCs" to "Competent Care to Three Distinct Populations: African-Americans, Asian-Americans, and Hispanic-Americans" to comply with the new requirements. There are many distinct populations that would be covered by the new Rule and the course offered at this site is in no way the only distinct populations that 681.140 addresses.

Another important change involves reporting of continuing education hours. According to the BHEC website: "Beginning January 1, 2026, all licensees must use CE Broker to track and report continuing education (CE) hours. Licensees will need to create an account and report continuing education before renewing their license." For more information about this requirement from the BHEC/Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors website, click here.

Most recent Consolidated Rulebook for LPCs. Click the picture below to see Rulebook.

INTRODUCTION:

There are currently over 25,000 active Licensed Professional Counselors in Texas. There are an additional 5,000 LPC Associates. Of this number, a small percentage of licensees will be cited for an ethics violation annually, but the total number of violations is not insignificant.

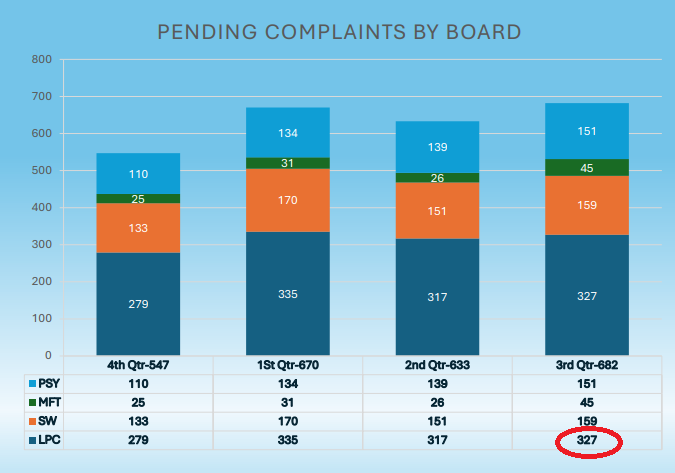

According to the BHEC Enforcement Status Report given at the Full Board Meeting of the TEXAS STATE BOARD OF EXAMINERS OF PROFESSIONAL COUNSELORS held on September 19, 2025, there were 279 total complaints pending against LPCs in Q4 of FY24. This number had increased to 327 by the third quarter of 2025.

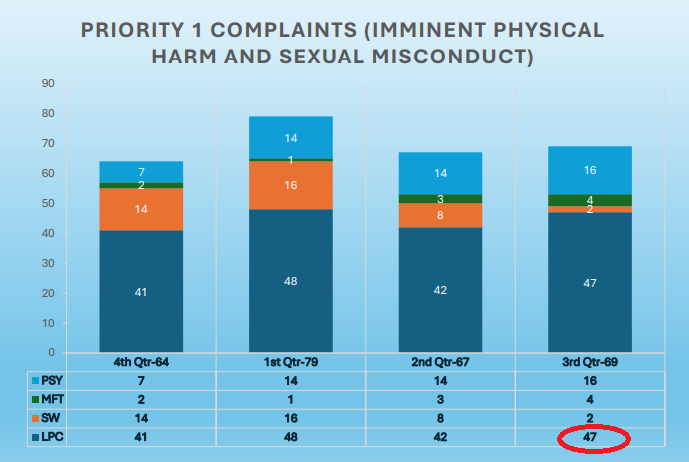

Almost 15% (41 out of 279) of the complaints in Q4 of 2024 involved imminent physical harm and sexual misconduct. The number of complaints in Q3 of 2025 had slightly increased to 47 representing 14% (47 out of 327) of total complaints.

Investigations can be lengthy and time-consuming for both licensees and BHEC staff. Although many complaints are dismissed or involve administrative penalties in the form of a fine, a serious violation has the potential to harm the welfare of a client, impact a community, damage the reputation of the profession, and result in loss of license by the licensee.

Many ethics standards seem to be common sense, while others are unlikely to be known intuitively and their application require careful study. Rules governing LPCs frequently change and can have significant conequences for those unfamiliar with the changes. For instance, the jurisprudence exam was previously a one-tme requirement, but is now required every renewal period for Texas LPCs. Staying informed and current can prevent problems with license renewal and an ethics violation. Fines related to failure to complete continuing education requirements has often been one of the most common infractions for licensees.

Knowledge of any particular ethics code does not guarantee ethical decision-making, but it is a starting point in the aim to prevent harm to the public. This course hopes to remind licensees of some of the obvious, and not-so obvious, ethical obligations Texas LPCs must fulfill.

Texas Statutory framework: Texas Administrative Code

The Texas Administrative Code (TAC) is a compilation of all state agency rules in Texas. Each title represents a subject category and related agencies are assigned to the appropriate title. The Texas Secretary of State compiles and maintains the Code. However, the Secretary of State does not interpret or enforce it. The rules applicable to Texas Licensed Professional Counselors are enforced by the Texas Behavioral Health Executive Council (BHEC) which adopts rules recommended by the Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors.

The overall purpose of the Texas Administrative Code, Chapter 681 (Professional Counselors), is to implement the provisions of Texas Occupations Code, Chapter 503 (the Licensed Professional Counselor Act), concerning the licensing and regulation of professional counselors.

Texas Administrative Code - Chapter 681 (Professional Counselors)

SUBCHAPTER B (Rules of Practice)

Texas Administrative Code (TAC), Chapter 681, SUBCHAPTER B, provides the rules of practice concerning the practice of professional counseling in Texas. SUBCHAPTER B covers various topics such as setting and maintaining appropriate professional boundaries, ensuring that all actions are in the best interest of the client, maintaining confidentiality, and avoiding financial or other situations that create a conflict of interest or other professional pitfalls, to name just a few. While the rules encompass a wide variety of subjects, they share one common goal and theme: LPCs must ensure that any action they take is in the client's best interest, rather than their own.

This course focuses on most, but not all, of the sections of Chapter 681, SUBCHAPTER B, which is divided into the following sections:

RULE 681.31, Counseling Methods and Practices

The practice of professional counseling is a nuanced field that relies heavily on the use of specific methods, techniques, and modalities to effectively address the diverse needs of clients. It is imperative that these approaches are employed by professional counselors who have received appropriate training and demonstrate competency in their application. This ensures not only the ethical delivery of services but also maximizes the efficacy of the interventions used. Authorized counseling methods may include various evidence-based modalities such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which focuses on identifying and altering negative thought patterns; person-centered therapy, which emphasizes unconditional positive regard and empathy; and solution-focused brief therapy, which targets specific goals and solutions rather than an emphasis on historical issues. Each of these methods requires a solid foundation of theoretical understanding and practical skill that can only be attained through rigorous education and supervised experience.

The dynamic nature of counseling necessitates that professionals remain aware of emerging techniques and evolving practices. This commitment to ongoing professional development ensures that counselors can offer the most current and effective therapeutic options. Adhering to ethical guidelines and professional standards is crucial; it not only protects clients but also enhances the counselor's credibility and effectiveness. Therefore, it is essential that counselors continuously engage in training and education related to their chosen modalities, as well as participate in peer supervision and consultation. Ultimately, the responsible and informed application of authorized methods fosters a therapeutic environment that promotes client growth, resilience, and well-being, reinforcing the profession's integrity and the foundational goal of facilitating meaningful change in individuals' lives.

Published in the Consolidated Rulebook, the Texas Administrative Code, section 681.31, states:

The use of specific methods, techniques, or modalities within the practice of professional counseling is limited to professional counselors appropriately trained and competent in the use of such methods, techniques, or modalities. Authorized counseling methods, techniques and modalities may include, but are not restricted to, the following…”1

Section 681.31 lists some of the authorized methods, techniques, and modalities professional counselors may use in practice. The authorized approaches mentioned in section 681.31 are not intended to be an exhaustive list. For instance, when a commenter; “requested §681.31 be amended to include EMDR as a counseling method,” the response was; “The Executive Council declines to amend §681.31 to specifically list EMDR as a counseling method. The rule is not intended to be an exhaustive list of all counseling methods, techniques, and modalities; and at this time there is not a need to add to the list of examples in this rule.”

Another point is that, just because a method or modality is listed, doesn’t mean a particular LPC has received adequate training in its use. In fact, it would be most likely impossible for a LPC to be adequately trained in the numerous counseling approaches and techniques available within all of the major theoretical categories: humanistic, cognitive, behavioral, psychoanalytic, constructionist and systemic.

Take a look at the modalities, techniques and approaches mentioned in Section 681.31. Which of these do you feel comfortable using with clients? Which ones might require additional training?

Individual counseling ● interpersonal ● cognitive ● cognitive-behavioral ● behavioral ● psychodynamic ● affective methods ● group counseling ● marriage/couples counseling ● family systems methods and strategies ● family counseling ● addictions counseling ● 12-step methods ● rehabilitation counseling ● education counseling ● career development counseling ● sexual issues counseling ● psychotherapy ● play therapy ● hypnotherapy ● music ● art ● dance movement ● techniques employing animals ● biofeedback ● formal and informal testing instruments and procedures ● consulting ● crisis counseling.

It’s important to evaluate one’s own training, experience, and competence, before using a counseling technique or approach. Practicing beyond one’s scope or without proper training is unethical. The American Counseling Association Code of Ethics provides guidance on several areas related to counseling methods and practices:

• Counselors have a responsibility to the public to engage in counseling practices that are based on rigorous research methodologies. (ACA Code of Ethics, Section C, Introduction)

• Counselors practice only within the boundaries of their competence, based on their education, training, supervised experience, state and national professional credentials, and appropriate professional experience. (ACA Code of Ethics, C.2.a.)

• Counselors practice in specialty areas new to them only after appropriate education, training, and supervised experience. While developing skills in new specialty areas, counselors take steps to ensure the competence of their work and protect others from possible harm. (ACA Code of Ethics, C.2.b.)

• Counselors accept employment only for positions for which they are qualified given their education, training, supervised experience, state and national professional credentials, and appropriate professional experience. Counselors hire for professional counseling positions only individuals who are qualified and competent for those positions. (ACA Code of Ethics, C.2.c.)

• Counselors continually monitor their effectiveness as professionals and take steps to improve when necessary. Counselors take reasonable steps to seek peer supervision to evaluate their efficacy as counselors. (ACA Code of Ethics, C.2.d.)

• Counselors take reasonable steps to consult with other counselors, the ACA Ethics and Professional Standards Department, or related professionals when they have questions regarding their ethical obligations or professional practice. (ACA Code of Ethics, C.2.e.)

• Counselors recognize the need for continuing education to acquire and maintain a reasonable level of awareness of current scientific and professional information in their fields of activity. Counselors maintain their competence in the skills they use, are open to new procedures, and remain informed regarding best practices for working with divere populations. (ACA Code of Ethics, C.2.f.)

• According to the ACA Code of Ethics; “If counselors lack the competence to be of professional assistance to clients, they avoid entering or continuing counseling relationships.” (ACA Code of Ethics, A.11.a.)

Regardless of the methods used, LPCs should be prepared to verify their training, experience, and clinical reasons for using a particular approach. In preparation to become an LPC, some counseling approaches would be adequately covered in most graduate programs, along with the required supervised work experience. Other methods might be more specialized and require additional training or certification.

The use of all modalities mentioned in 681.31 are limited to professional counselors; “appropriately trained and competent in the use of such methods, techniques, or modalities.” There are some additional requirements for a few of the techniques mentioned.

For example, according to 681.21(15), counselors using biofeedback; “must be able to prove academic preparation and supervision in the use of the equipment as part of the counselor’s academic program or the substantial equivalent provided through approved continuing education.”

LPCs who use assessment and appraisal related to testing must be in compliance with the criteria listed in Section 681.43. Consulting, according to 681.31 (17) uses; “the application of specific principles and procedures.”

Other than general terms like; “appropriately trained” and “competent,” the specifics of how a licensee would demonstrate competence for the approaches cited in Section 681.31 is not spelled out. Counselors should assume the burden of proof rests on them when demonstrating competence in a particular area.

The same type of considerations specifically mentioned for the use of biofeedback, test administration, and consulting, would be part of the many items for consideration applying to cognitive-behavioral therapy, family counseling, play therapy, or any of the many other approaches mentioned in Section 681.31.

If an LPC’s counseling methods or techniques have been questioned by a client, colleague, supervisor, or as the result of a complaint filed with the BHEC, licensees should be prepared ahead of time to provide a thorough response that includes verification of adequate training, experience, and knowledge of research, that supports the approach.

Some helpful questions to consider when determining one’s ability to treat a client, or the approach that should be used, might include the following:

• Am I practicing within the policies and procedures of the agency where I am employed?

• Can I verify that I have been trained and gained adequate experience to treat this population or diagnosis?

• Am I using methods, practices, and techniques that are up-to-date, considered best practice, and validated by research?

• If I am unsure of my competence, have I consulted with colleagues or supervisors on the matter?

• Do I have an on-going procedure in place to assess my counseling efficacy through peer supervision or consultation?

To drive home the point and importance to avoid practicing beyond one’s scope, one legal entity identified the following as two common reasons for malpractice lawsuits filed against counselors; 1) the use of techniques without proper training and; 2) failing to consult with peers or to take advice from peers.2

Not only are counselors challenged to ensure their competencies match the needs of clients at the time of admission to services, clients may present issues that emerge later on in the counseling process that may require a referral. For instance, a client may indicate a primary need for help with panic attacks and reveal several sessions later that he or she has been abusing alcohol daily.

Just as an oncologist would refer a patient with cardiac problems to a cardiologist, LPCs must continually assess the match between their own competencies and the needs of clients.

The acquisition and evaluation of up-to-date skills through additional certifications, continuing education, experience and other means, should be on-going for all counselors. A counselor’s scope of practice should always consider the client’s needs and prevent harm.

Harmful Counseling Techniques

Arguably, many counseling methods or techniques could be ineffective, ill-advised, or even dangerous, if used improperly in a given situation with a particular client. Glenys Parry, a professor and chief investigator of a government funded study in England probing the harm of some therapies, concluded that most people are helped by therapy, but added, “anything that has real effectiveness, that has transformative power to change your life, has also got the ability to make things worse if it is misapplied or it's the wrong treatment or it's not done correctly."3

Harmful counseling practices can significantly undermine the therapeutic process and negatively impact clients' mental health and well-being. One such practice is the imposition of personal beliefs and values on clients. When counselors prioritize their own perspectives over the client's lived experiences, it creates a power imbalance that can stifle open communication and discourage clients from expressing their true feelings.

Additionally, neglecting to establish a safe and supportive environment can lead to feelings of vulnerability and mistrust, further alienating individuals seeking help.

Another detrimental practice is the reliance on outdated or unverified techniques that lack empirical support. For example, implementing interventions without tailoring them to the unique context and needs of the client can obstruct progress and leave individuals feeling misunderstood or neglected.

Furthermore, a lack of cultural competence can manifest as an insensitivity to the diverse backgrounds of clients, which may alienate them and prevent beneficial engagement in the counseling process.

Finally, ignoring ethical boundaries, such as dual relationships or breaches of confidentiality, can severely damage the client-counselor relationship. Such violations erode trust and can lead to lasting harm, discouraging individuals from seeking help in the future. It is crucial for counseling professionals to remain vigilant about these harmful practices to foster a therapeutic environment that prioritizes clients' safety, respect, and empowerment.

Some occurrences of counseling malpractice illustrate the potential for severe consequences. For example, a young girl was smothered to death in a rebirthing session despite prior evidence the technique was harming the child. The unlicensed “counselor” was applying rebirthing therapy in the course of attachment therapy with aid of the girl’s mother and three assistants (Nicholson, 2001). Rebirthing has been banned in some states and opposed or not recognized as viable treatment by professional organizations in others.

The Example of Recovered Memory

The recovery of repressed memories of child abuse became popular in the early 1980’s. A wave of prosecutions and lawsuits against alleged perpetrators followed. At the same time, many children provided accounts of current or recent abuse as well.

In the 1990’s a wave of malpractice claims against counselors and organizations accused of eliciting false memories followed. The recovered memories were often elicited through manipulative interrogation techniques directed at children. The incidents were often unsupportable by evidence or even extremely improbable.

Many feel that this period constituted a modern witch-hunt. In Manhattan Beach, California, as the McMartin Preschool case was unfolding, many cars displayed bumper stickers saying, “We Believe the Children.” Smear campaigns were directed at people who questioned the recovered memory movement.

As experts came to understand the situation better, more sober discussions ensued, buoyed by research. Many recognized that it was possible to inadvertently, or purposely, manipulate children during assessments. Guidelines for interviewing children and for assessing symptoms were developed with this in mind. Much research has clarified the nature of memory, therapy, and testimony relevant to this issue.4 Successful cases against counselors using inappropriate means of producing memories of childhood abuse resulted in large penalties in the 1990s.

The wave of repressed memory and questionable abuse cases peaked in the mid 1990’s, and have diminished as a result of research and increased sophistication in the courts, social services, the public, and counseling.

Challenges of Evidence-Based Practice

The emphasis on evidence-based therapies (EBTs) in the field of counseling has increased with time. EBTs are often used to establish the evaluation of academic programs, requirements for licensure, how counselor competence is assessed, and how reimbursement policies are structured.

Researchers have pointed out the inherent limitations of randomized control trials to adequately define and measure psychological problems, the generalizability of findings, the under representation of clients with comorbid conditions, and the confounding nature and impact of psychosocial stressors on research subjects, to name a few. Nevertheless, clinicians face increasing challenges to justify their approaches in terms of evidence such as outcome studies and other research published in peer-reviewed journals5

Experts may raise concerns regarding inadequate training in evidence-based practice on the part of academic institutions. However, there are significant challenges in attempting to fulfill this aspiration.5

There can be difficulty; “converting clinical guidelines into active performance measures,” or in, “integration of findings into daily operations.”5 Research may not apply to psychotherapy in the field as well as intended. Counselors in research studies may not actually carry out therapy with as much fidelity to the prescribed method as is believed, because they may put clients’ needs ahead of the research objectives, or because the client cohort is not as homogenous as they appeared to be during enlistment of subjects.

Often, there is not enough consistent data available to form a secure evidence-based opinion, despite the existence of practice guidelines and texts that synthesize what information is available. Research can’t always keep up with clinical innovation and the diversity of clients.

Staying up-to-date is the first priority in evidence-based practice. However, it is important to remember that the integrity of research is often limited by problems such as bias and weak methods. Statistically weak results may be presented as though they are newsworthy.

As a result, many methods must gain credibility through clinical experience. However, licensees can avoid acting on blind faith by staying outcome-focused. We must carefully assess risks and our own scope of practice and competence.

RULE 681.35

Informed Consent

Informed consent is a foundational aspect of ethical counseling, ensuring that clients are fully aware of the services they will receive, the risks involved, and their rights in the therapeutic relationship. However, there are instances where counselors have failed to uphold the standards set forth in regulations in Texas Administrative Code (TAC) 681.41. For example, a counselor working in a school setting failed to inform a student and their parents about the nature of the counseling services, including the limitations of confidentiality and the potential for information sharing. This oversight led to a breach of trust when sensitive information was later disclosed without parental consent.

Another example involves a private practice counselor who did not provide clients with clear information about therapy fees, session duration, and the overall treatment process. This lack of transparency left clients feeling misled and uncertain about their financial commitment and expectations for treatment, ultimately jeopardizing the therapeutic alliance. Additionally, a marriage and family therapist neglected to explain the implications and risks associated with couple’s therapy, particularly regarding how individual sessions might affect the dynamics of the relationship. This failure to provide adequate informed consent led to conflict and dissatisfaction among the couple as they struggled with unresolved issues that were not addressed in therapy.

Lastly, a counselor specializing in substance abuse recovery failed to adequately inform clients about the potential consequences of disclosing personal information during group therapy sessions. The counselor did not emphasize that confidentiality could not be guaranteed in such a setting, which resulted in several participants feeling exposed and vulnerable after their experiences were shared outside the group by other members. These examples underscore the critical importance of thorough and clear informed consent practices in counseling, as failure to comply can lead to significant consequences for both clients and practitioners.

In Texas, there are certain requirements that must be met by licensees before a professional relationship is established and counseling services can begin. According to TAC 681.41, regardless of the setting, licensees must provide counseling only in the context of a professional relationship. This includes having clients complete an informed consent, signed written receipt of information, or in the case of involuntary treatment a copy of the appropriate court order.

Other requirements of informed consent include the following:

(1) fees and arrangements for payment;

(2) counseling purposes, goals, and techniques;

(3) any restrictions placed on the license by the Council;

(4) the limits on confidentiality;

(5) any intent of the licensee to use another individual to provide counseling treatment intervention to the client;

(6) supervision of the licensee by another licensed health care professional including the name, address, contact information and qualifications of the supervisor;

(7) the name, address and telephone number of the Council for the purpose of reporting violations of the Act or this chapter; and

(8) the established plan for the custody and control of the client's mental health records in the event of the licensee's death or incapacity, or the termination of the licensee's counseling practice.

Rule 681.35 also states:

(b) A licensee must inform the client in writing of any changes to the items in subsection of this section, prior to initiating the change.

(c) Prior to the commencement of counseling services to a minor client who is named in a custody agreement or court order, a licensee must obtain and review a current copy of the custody agreement or court order, as well as any applicable part of the divorce decree. A licensee must maintain these documents in the client's record and abide by the documents at all times. When federal or state statutes provide an exemption to secure consent of a parent or guardian prior to providing services to a minor, a licensee must follow the protocol set forth in such federal or state statutes.

(d) A licensee acting within the scope of employment with an agency or institution is not required to obtain a signed informed consent, but must document, in writing, that the licensee informed the client of the information required by subsection (a) of this section and that the client consented.

These requirements are some of many that help inform clients about the nature of the relationship and the obligations of the counselor. Some of the items may take a few minutes to explain. Others, for instance; “counseling purposes, goals, and techniques,” may require on-going explanation and re-evaluation throughout the counseling process. These are just some of the many aspects that help to create and maintain a professional relationship with clients.

Informed consent involves the clear and thorough explanation of all services provided. It is an on-going process. In addition to the areas mentioned above, other areas to consider for the informed consent process include the following:

• Qualifications of Counselor(s)

• Eligibility of client for services

• Counseling Sessions/Missed or Late Cancelation Appointments

• Risks of Counseling

• The Boundaries of a Therapeutic Relationship

• Electronic Communication

• Your Rights as a Client

• Cooperation of Client

• Rates

• Insurance

• Miscellaneous Fees

• Referrals

• Records

• After-Hours Emergencies

• Therapist’s Incapacity or Death

• Acknowledgment and Statement of Understanding

• Client Satisfaction Surveys

• The nature and purpose of treatment

• Potential benefits of treatment

• Limits to treatment

• Treatment alternatives

• Risks associated with not receiving treatment

• The clients’ right to refuse to consent or to revoke their consent at any time

ADDITIONAL ASPECTS OF A PROFESSIONAL RELATIONSHIP

One of the main purposes of Chapter 681 is to help licensees adopt practices that maintain a professional relationship with clients. Anytime a counselor decides to make the relationship something other than a professional one, there is greater potential for harm to the client.

It could be argued that almost every topic or situation codified in Chapter 681 is intended to safeguard the professional relationship from becoming something other than therapeutic for the client.

PROFESSIONAL VALUES

A professional relationship requires professional values to be upheld by the licensee. In order for something to have value, it has to be important and something to which we are committed. Ethical decisions are much more likely to be one’s approach if there is a commitment to live out our commitment to work in the client’s best interest.

The ACA Code of Ethics Preamble identifies the following as core professional values:

enhancing human development throughout the life span; honoring diversity and embracing a multicultural approach in support of the worth, dignity, potential, and uniqueness of people within their social and cultural contexts; promoting social justice; safeguarding the integrity of the counselor–client relationship; and practicing in a competent and ethical manner.

While professional values are internal, they are the root and motivation of principles we demonstrate externally through our actions. According to ACA, the fundamental principles of professional ethical behavior are:

The ACA’s fundamental principles include:

-Autonomy, or fostering the right of the client to control the direction of one’s life;

-Nonmaleficence, or avoiding actions that cause harm to the client;

-Beneficence, or working for the good of the individual and society by promoting mental

health and well-being;

-Justice, or treating individuals equitably and fostering fairness and equality;

-Fidelity, or honoring commitments and keeping promises, including fulfilling one’s responsibilities of trust in professional relationships; and

-Veracity, or dealing truthfully with individuals with whom counselors come into professional contact.

FIDUCIARY RESPONSIBILITY

Many different kinds of relationships, particularly professional relationships, involve a fiduciary duty. A fiduciary duty is a duty imposed, generally, on the more powerful party to act in the best interest of the less powerful party. A lawyer, for example, has a fiduciary duty to her clients, who place their trust and confidence in her hands; she has special expertise they do not, and they retain her and pay her fees with the understanding that she will use that expertise to represent their interests.

Similarly, a physician has a fiduciary duty to his patients: They seek her medical advice because she has the specialized knowledge and skill necessary to deal with their health problems in ways that they cannot – and, again, they pay her fees in the expectation that she will use that knowledge and skill to make them well.

Fiduciary responsibility comes in many forms. Fiduciaries include physicians, attorneys, teachers, financial advisors, parents, real estate agents, and just about anyone who owes a duty of care, loyalty, good faith, confidentiality, prudence, and disclosure to someone.

As mentioned throughout this course, the primary objective of counselor ethics is to protect clients and work in their best interests to assist them in meeting their counseling goals. The ACA identifies one of the purposes of its Code of Ethics to be the following: “The Code serves as an ethical guide designed to assist members in constructing a course of action that best serves those utilizing counseling services and establishes expectations of conduct with a primary emphasis on the role of the professional counselor.”

Fiduciary responsibility may include the following:

Duty of Care: This pertains to being competent to provide the help clients need. It involves sound judgment in making decisions to assist the client. It offers options that reflect sensible decision-making. This means that LPCs must engage in continuous education and training to enhance their skills, enabling them to apply sound judgment in assessing clients' needs. By offering well-considered options that reflect prudent decision-making, counselors help clients navigate their challenges with informed guidance.

Duty of Loyalty: This pertains to acting in the best interest of the beneficiary at all times and correcting any possible conflicts of interests. Duty of Loyalty mandates that LPCs prioritize their clients' interests above all else. This involves actively identifying and correcting any potential conflicts of interest that may arise during the therapeutic relationship. By maintaining unwavering loyalty, counselors foster an environment built on trust, assuring clients that their welfare is paramount.

Duty of Good Faith: Licensees always act to the benefit of the client and within the confines of the law. Duty of Good Faith requires counselors to act honestly and ethically, consistently pursuing actions that benefit clients while adhering to legal stipulations. This duty reinforces the integrity of the counseling profession, creating a framework within which clients can confidently explore their thoughts and emotions.

Duty of Confidentiality: Confidentiality is the cornerstone of the counseling relationship. It is never violated except when it is required by law in specific situations. LPCs must rigorously protect the privacy of their clients, disclosing information only when legally mandated or ethically justified. By safeguarding this sensitive information, counselors build a strong rapport with clients, encouraging openness and vulnerability.

Duty of Prudence: Fiduciaries use good judgment and carefully weigh the risks of any decisions impacting the client. The Duty of Prudence compels LPCs to exercise careful judgment when making decisions that affect their clients. This involves weighing potential risks and benefits to ensure that the client's best interests are always front and center.

Duty to Disclose: Fiduciaries are transparent with clients in disclosing information that can impact clients and their ability to carry out their duties. The Duty to Disclose mandates transparency between counselors and clients. LPCs must communicate relevant information that could impact clients' understanding of their treatment and the counselor's professional obligations. By ensuring that clients are well-informed, counselors empower them to make educated choices about their therapeutic journey.

Collectively, these fiduciary responsibilities ensure that Texas LPCs provide ethical, effective, and client-centered care, fostering a therapeutic alliance that is both supportive and constructive.

RULE 681.36

Client Records

In the practice of licensed counseling and therapy, meticulous record-keeping is essential to ensure that each client receives appropriate care and that the therapist complies with legal and ethical guidelines. For each client, a licensee must maintain accurate records that include various critical documents. For instance, the signed informed consent is fundamental, reflecting the client's understanding and agreement to the treatment process. In cases of involuntary treatment, a copy of the court order is necessary to validate the intervention. Additionally, the intake assessment provides a comprehensive overview of the client's psychological and emotional state upon entry into the program.

Furthermore, documenting the dates of counseling treatment interventions is crucial for both tracking progress and scheduling future appointments. Effective treatment often relies on specific methodologies; therefore, licensees need to record principal treatment methods employed during sessions, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or motivational interviewing. Progress notes are also integral to monitoring the client’s development and adapting the treatment plan as necessary. Each client record must include a detailed treatment plan that outlines the therapeutic goals and strategies tailored to the individual's needs. Lastly, accurate billing information is vital for ensuring that the practice complies with financial regulations and for clear communication with clients regarding the cost of services.

In terms of record retention, it is important to note that, in the absence of specific state or federal laws, records must be maintained for a minimum of seven years following the termination of services. Alternatively, if a client reaches the age of majority, records should be kept for five years after that date, whichever period is longer. This guideline is designed to safeguard client information and ensures that relevant data remains available for any future consultations or legal matters.

Additionally, records generated by a licensee during their employment with an agency or institution are typically maintained by the respective employer. However, if the employer does not retain these records, it becomes the responsibility of the licensee to ensure they are preserved and managed appropriately. This stipulation emphasizes the importance of organizational protocols in handling sensitive client information while placing responsibility on individual licensees to uphold ethical and professional standards in their practice.

RULE 681.37

Billing and Financial Arrangements

Billing requirements play a crucial role in ensuring transparency and integrity within therapeutic and counseling practices. For instance, a licensee must charge clients solely for services that have been rendered or for services that both the client and the licensee explicitly agreed upon at the onset or through mutual written modifications. An example of proper billing would be a therapist who provides weekly sessions and closely documents the enhancements to the treatment plan that may necessitate additional sessions, thus adequately reflecting all charges on the billing statement.

Additionally, clients and their guardians have the right to request a plain-language explanation of previous charges made for counseling services. For example, if a parent requests this information for their minor child, the licensee must provide a clear breakdown of each treatment charge, avoiding any jargon or technical terms that might confuse the client or guardian. This practice supports informed consent and empowers the client or guardian to understand the financial implications of the treatment received. It should also be noted that overcharging clients is strictly prohibited; hence, a licensee who charges higher than the agreed fee for a session or service could face ethical and legal repercussions. Furthermore, licensees are not allowed to submit bills for treatments that they know or should know are unwarranted. This might include billing for a service that, upon reflection, does not align with the client's treatment goals or was never actually administered, although cancellations may be billed accordingly.

In addition to billing integrity, the ethical considerations extend into relationships with potential referral sources. Under Texas law, a licensee is prohibited from offering or accepting any form of remuneration for securing or soliciting clients. This regulation ensures that the focus remains on providing the best care to clients without the interference of financial incentives that could lead to conflicts of interest.

Licensees working under contracts with chemical dependency or mental health facilities must also comply with specific stipulations outlined in the Texas Health and Safety Code regarding solicitation and contracting practices. By following such stringent guidelines, licensees ensure their practices adhere to state laws regarding marketing and remuneration, fostering a safe and ethical environment for client care.

NOTE: In the Rulebook dated March 24,2025, the following has been deleted from Rule 681.37 regarding Billing and Financial Arrangements at the end of paragraph (c) in green highlight:

(c) A licensee employed or under contract with a chemical dependency facility or a mental health facility must comply with the requirements in the Texas Health and Safety Code, §164.006, relating to soliciting and contracting with certain referral sources. [Compliance with the Treatment Facilities Marketing Practices Act, Texas Health and Safety Code Chapter 164, will not be considered as a violation of state law relating to illegal remuneration.]

Reasoned Justification.

The adopted amendments remove language identified during the quadrennial rule review to better align with the agency's statute.

RULE 681.38

Conflicts, Boundaries, Dual Relationships and Termination of Relationships

"A licensee must not engage in activities for the licensee's personal gain at the expense of a client."

Texas Administrative Code 681.38(a) establishes a crucial ethical standard for licensed professionals, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing client welfare above personal interests. This regulation mandates that licensees must refrain from engaging in any activities that could benefit themselves financially or otherwise at the expense of their clients. For instance, a therapist must avoid the temptation to recommend unnecessary treatments or sessions solely to increase their income, instead focusing on the client's best therapeutic interests.

681.38(a) acts as a fundamental guideline that reinforces the ethical responsibilities of licensees, fostering a professional environment where clients’ welfare is the top priority.

According to paragraph (b), a licensee is permitted to promote their personal or business activities to clients if these offerings are designed to enhance the counseling process or assist clients in reaching their counseling objectives. However, before initiating any engagement related to these activities, the licensee is required to disclose their personal or business interests to the client transparently. This disclosure is crucial to maintain ethical standards and ensure that clients are fully informed about any potential conflicts of interest. Moreover, the licensee must avoid exerting undue influence when encouraging clients to consider these activities, services, or products, thereby safeguarding the clients' autonomy and decision-making in the counseling relationship.

(c) A licensee must set and maintain professional boundaries.

Professional boundaries encompasses many aspects of behavior for Texas licensed professional counselors. Professional boundaries include essential components that ensure the integrity of the therapeutic relationship and the well-being of clients. These boundaries delineate the space between the counselor's professional responsibilities and personal inclinations, safeguarding the client from potential harm and exploitation.

Counselors must maintain a clear distinction between their professional roles and personal relationships, avoiding dual relationships that could impair their objectivity or create conflicts of interest. For instance, engaging in social interactions with clients outside the therapeutic setting or providing services to friends or family can jeopardize the therapeutic alliance and undermine the counselor's effectiveness.

In Texas, licensed professional counselors are also mandated to adhere to professional boundaries that emphasize respect for clients’ autonomy and confidentiality. This includes obtaining informed consent before sharing any information about the client with third parties. Counselors must also be attentive to their own vulnerabilities and biases, as these elements can inadvertently skew the counseling process. Establishing professional boundaries helps create a safe and supportive environment for clients to explore their thoughts and feelings, fostering trust and promoting therapeutic progress.

Furthermore, Texas licensed professional counselors are expected to maintain appropriate limits in their interactions with clients, particularly concerning physical touch, personal disclosures, and emotional support. These boundaries not only protect clients but also help counselors manage their own emotional states and prevent burnout. Counselors should engage in regular supervision and reflection to assess how they are managing these boundaries, ensuring that they remain attuned to the needs of their clients while safeguarding their own well-being and professional integrity. Upholding these professional boundaries is crucial in fostering a therapeutic environment that promotes healing, growth, and positive change.

Included in professional boundaries is the prohibition against non-therapeutic relationships with clients. The distinction between therapeutic and non-therapeutic relationships is crucial. A non-therapeutic relationship refers to any interaction that occurs outside the scope of counseling, whether initiated by the client or the licensee.

Such relationships can blur the lines between professional and personal boundaries, potentially complicating the therapeutic process. Because of the inherent power dynamics and potential for exploitation in a client-licensee relationship, ethical guidelines stipulate that a counselor may not engage in a non-therapeutic relationship with a client for a minimum of two years after the formal counseling relationship has concluded. This waiting period is designed to protect the integrity of the counseling framework and ensure that the client is not vulnerable during a critical transitional phase.

Moreover, specific prohibitions apply to romantic or sexual relationships with clients, which must remain off-limits for five years after the conclusion of the counseling relationship. Recognizing the emotional intensity and potential dependency that can arise during therapy, this extended period aims to safeguard the client's well-being and mitigate any risk of exploitation or coercion. If a licensee wishes to engage in a non-therapeutic relationship after this period, they carry the burden of proof to demonstrate that the relationship was consensual and not manipulative. Additionally, they must show that the relationship is not detrimental to the client, taking into consideration various factors outlined in regulatory guidelines.

Finally, ethical standards dictate that a licensee must refrain from providing counseling services to family members, personal friends, educational associates, or business associates. This policy prevents conflicts of interest and ensures that professional boundaries remain intact. By maintaining these boundaries, counselors can uphold the trust and safety necessary for effective therapeutic interventions, ultimately prioritizing the client's mental health and welfare over personal or familial connections.

Additional professional boundaries included in Rule 681.37 states that Texas LPCs are prohibited from giving or receiving gifts valued at more than $50. Additionally, licensees must refrain from borrowing or lending money or items of value to clients or their relatives. Furthermore, the acceptance of payment in the form of goods or services instead of monetary compensation is also forbidden. These regulations are designed to foster trust and transparency in client interactions, ultimately protecting both the client and the professional's integrity.

Licensees are prohibited from engaging in non-professional relationships with a client's family members or individuals connected to the client if such relationships could harm the client. This guideline underscores the importance of safeguarding the client's well-being by preventing conflicts of interest and emotional complications.

Seeing More Than One Therapist

Licensees must refrain from providing counseling to individuals who are already receiving therapy from another mental health provider unless they have the knowledge and consent of that provider. This requirement emphasizes the need for collaboration among professionals to ensure that the client receives comprehensive care without conflicting interventions. If the licensee discovers that a client is undergoing concurrent therapy, they must seek the client's permission to communicate with the other professional, aiming to foster positive and cooperative relationships.

A licensee who is willing to treat a client concurrently with another counselor must first obtain permission from the other clinician. Clients should not receive concurrent counseling without both therapists’ approval.

There could be situations when a client fails to tell one or both therapists of the concurrent treatment, but if it is discovered, the licensees must seek release from the client to work collaboratively.

The licensee must not knowingly offer or provide counseling to an individual concurrently receiving counseling treatment intervention from another mental health services provider except with that provider's knowledge. If a licensee learns of such concurrent therapy, the licensee must request release from the client to inform the other professional and strive to establish positive and collaborative professional relationships.

The American Counseling Association’s Code of Ethics is similar:

When counselors learn that their clients are in a professional relationship with other mental health professionals, they request release from clients to inform the other professionals and strive to establish positive and collaborative professional relationships. (A.3.)

There are no laws or regulations that strictly prohibit a client from seeing one or more therapists at the same time. Some clients believe they benefit from the arrangement, but the monetary cost alone would prevent many from doing so.

The practice of using multiple therapists can be a part of strategic counseling services. The licensee may believe the client would benefit from a specialized approach used by another counselor to address certain issues, but would like to continue treatment with the client to address other issues. Clients with dual diagnoses might especially present these kinds of treatment scenarios.

Some therapists are opposed to concurrent therapy. The potential for incongruent objectives, splitting by the client, extra time required for collaboration with another counselor, or problems working through transference with the client, might be a few reasons for opposing it. Although not entirely analogous, they may see it as similar to a client seeing multiple prescribers of medication for the same condition.

In summary, concurrent therapy may be beneficial for some clients as long as the two professionals agreed to it, respect professional boundaries, and work collaboratively so the client does not receive conflicting or confusing advice.

Furthermore, a licensee is obligated to terminate a professional counseling relationship if it appears that the client is not benefiting from the sessions. This commitment to client welfare requires the counselor to be vigilant about the effectiveness of their methods and to prioritize the client’s best interests.

When termination of the relationship becomes necessary, the licensee must take proactive steps to facilitate the client's transfer to appropriate care, ensuring continuity and support in the pursuit of mental health. These guidelines collectively highlight the ethical responsibility of counselors to maintain professional integrity and prioritize the well-being of their clients throughout the therapeutic process.

More on Professional Relationships

In general, a professional relationship is one in which the parameters and goals of the relationship are clearly defined, understood, and agreed upon by the licensee and client. A professional relationship is one in which the licensee always works for the best interests of the client.

According to the Texas Administrative Code, Licensed Professional Counselors (LPCs) are required to provide counseling exclusively within the framework of a professional relationship. This regulation emphasizes the importance of establishing a structured and ethical connection between the counselor and the client, which is essential for effective therapeutic work. A professional relationship is characterized by clear boundaries, mutual respect, and trust, creating a safe environment where clients can explore their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Such a setting not only facilitates the therapeutic process but also safeguards both the counselor and the client from potential conflicts of interest and ethical dilemmas.

The American Counseling Association (ACA) further elaborates on the essence of counseling by defining it as a professional relationship designed to empower diverse individuals, families, and groups. This definition highlights the multifaceted nature of counseling, which encompasses not only mental health support but also guidance in wellness, education, and career aspirations. This empowerment is particularly crucial in a diverse society where individuals face varying challenges and barriers. The professional relationship fosters an atmosphere of collaboration, enabling clients to set and achieve personal goals while receiving tailored support that respects their unique backgrounds and experiences. By adhering to these principles, LPCs uphold the integrity of the counseling profession and contribute to the overall well-being of their clients.

Moreover, the stipulation that counseling activities must occur within a professional context serves to reinforce the ethical standards upheld by the counseling profession. It acts as a safeguard against the potential for dual relationships that could complicate the therapeutic process and undermine the trust essential for effective counseling. For example, engaging in social or personal relationships with clients outside the counseling sessions could lead to biases, exploitation, or breaches of confidentiality. Therefore,

Texas LPCs must navigate carefully the boundaries of professional relationships, ensuring that their practice not only adheres to legal regulations but also aligns with the core values of respect, integrity, and professionalism as outlined by organizations like the ACA. In doing so, they enhance the effectiveness of their interventions and the overall quality of care provided to their clients.

Non-Therapeutic Relationships

The TAC defines a non-therapeutic relationship as: any non-counseling activity initiated by either the licensee or client that results in a relationship unrelated to therapy.

It does not take a great deal of discernment to understand the predicament in which licensees could find themselves by choosing to engage in a non-therapeutic relationship with a current or former client, or engaging in sexual exploitation or sexual contact with a client, former client, LPC Associate, or student.

As already mentioned, the TAC defines ‘non-therapeutic’ as any non-counseling activity initiated by either the licensee or client that results in a relationship unrelated to therapy. The line between ‘therapeutic’ or ‘non-therapeutic’, as well as ‘related to counseling’ or ‘not related counseling’, might be straight forward in most cases, but not all.

For instance, some licensees would consider visiting a client in the hospital, or attending a client’s wedding or graduation, to be therapeutic and related to therapy. Other licensees might feel uncomfortable doing so in almost all cases. Much would depend on the context and the relevant factors already cited. The ACA Code of Ethics mentions all of these examples (weddings, graduations, funerals) as potentially permissible within the therapeutic relationship, as long as certain precautions are taken.

Set standards for acceptable behavior within the professional relationship include within them an allowance for certain situations that may fall outside a typical professional relationship. However, these situations, if ventured into, may be permissible, but potentially require considerable justification by the licensee.

When boundaries are extended for certain events as weddings or funerals, the ACA Code of Ethics advises counselors to “take appropriate professional precautions such as informed consent, consultation, supervision, and documentation to ensure that judgment is not impaired and no harm occurs.”

In addition, the ACA Code advises that, when counselors extend boundaries, they must officially document, prior to the interaction (when feasible), the rationale for such an interaction, the potential benefit, and anticipated consequences for the client or former client and other individuals significantly involved with the client or former client.

The burden of proof rests on the licensee to justify any relationship outside normal counseling parameters cited in TAC and all other applicable laws.

POTENTIAL HARM OF DUAL RELATIONSHIPS

The primary concern about dual roles played by a therapist is the potential (or actual) damage that is done to the client as a result of crossing or violating boundaries (both sexual and non-sexual). Wheeler and Bertram describe five categories where this damage may be seen6:

• Loss of objectivity or clarity. Dual relationships can add a layer of distraction to a professional relationship that is inherently already filled with challenges to objectivity and clarity. Most mental health professionals recognize that counseling and psychotherapy are subjective endeavors. Objectivity is not really possible: Perception is influenced by a host of conscious and unconscious, social, cultural, political, and life experiences variables. During graduate training, post-degree supervision, and ongoing colleague consultation, counselors are constantly striving to maintain as much clarity as possible in interacting with clients. The loss of objectivity/clarity may be consciously recognized by the counselor, or it can occur below the counselor’s awareness. In any event, the loss of objectivity and clarity represents a dynamic in the counseling office that prevents the counselor from being fully present for the client and challenges the ethically mandated primary responsibility of the counselor to respect the dignity and promote the welfare of clients. Dual relationships represent another layer of distraction that a counselor must sort through in order to maintain an acceptable level of objectivity and clarity.

• Potential for misunderstanding. Misunderstanding between human beings is natural and inevitable. Under normal circumstances, misunderstandings that occur within a counseling relationship can be worked through and often can become important diagnostic and therapeutic opportunities. When a counseling relationship is intertwined within a dual relationship there is increased opportunity for misunderstanding. Interactions that occur in the nonclinical relationships can create misunderstanding within the counseling relationship and vice versa. In human interactions, misunderstandings can quickly multiply, with one misunderstanding feeding on another until there is a breakdown of the counseling relationship. We are ethically charged to do no harm and whenever possible to minimize or to remedy unavoidable or unanticipated harm; misunderstanding fueled by a dual relationship frequently can be a conduit to client harm.

• Conflict of Interest. Co-occurring or sequential dual roles can create a conflict of interest, a situation in which a counselor (or someone or something important to the counselor) can be affected by decisions or behaviors in the client is contemplating. A conflict of interest can tempt a counselor to use the power of the counseling relationship to sway the client in a direction preferred by the counselor. Such inappropriate influence can easily result in harm to the client. Even if the counselor resists the temptation to inappropriately influence the client, the treatment relationship can still be affected. The client may wonder about the counselor’s motives, and the counselor might have some conflicted feelings for having to defer his or her own best interest in favor of the client’s.

• Breach of confidentiality and privacy. When clinical and nonclinical roles become intertwined, it becomes difficult for counselors to remember what information may be discussed. When non-counseling roles are informal or intense (friendships, social groups, business or work relationships, etc.), the likelihood of a breach of confidentiality and a violation of the client’s right of privacy dramatically increases.

• Exploitation. Mental health professionals who intentionally misuse the power differential inherent within the counseling relationship to take advantage of a client or former client are behaving in an abusive and exploitive manner. These situations tend to be the most ethically and legally egregious and often involve sexual or financial exploitation. These dual relationships are not innocent; they are not just a momentary lapse in judgment. They are the basis for real harm to the client as well as ethical and legal consequences to the counselor, including ethics complaints, licensing board disciplines, malpractice lawsuits, and possibly felony imprisonment.”

Dual relationships can include sharing meals with a client; visiting a client's home; inviting the client to visit one's own home; socializing at a party, sporting event, or other activity; or other professional or employment-related affiliations.

Experts counsel LPCs not to see clients outside of the consulting context and to avoid development of social relationships that can adversely affect the therapeutic process. Likewise, LPCs should not accept as a client any individual with whom the LPC has previously interacted in a social context.

RULE 681.41

General Ethical Requirements

Honest and accurate representation of one’s credentials, abilities, and possible outcomes with clients is essential for licensees. There are varying degrees of claims that can mislead or injure clients. “Stretching the truth” is not a minor issue. Think how even a misleading statement in a casual conversation with a colleague or friend can injure the trust we have in them and their abilities.

Clients served by counselors are often in a heightened position of vulnerability and need protection from deceptive statements about how they will respond to treatment. A depressed client who has been misled into believing a particular approach is certain to work may assume it is their fault that they have not responded as promised, or may lose hope that another approach might help.

Rule 681.41 prohibits licensees from exaggerating their credentials or expressing certitude that they can help a client. Licensees must present themselves and their services with much discretion.

According to 681.41 (a), A licensee must not make any false, misleading, deceptive, fraudulent or exaggerated claim or statement about the licensee’s services, including, but not limited to:

1) the effectiveness of services;

2) the licensee’s qualifications, capabilities, background, training, experience, education, professional affiliations, fees, products, or publications; or

(3) the practice or field of counseling.

In the context of Texas Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC) claims, exaggerated assertions can significantly undermine the integrity of the profession and violate the Texas Administrative Code, which mandates that LPCs must not misrepresent their qualifications or the effectiveness of their services. Exaggerated claims can manifest in various forms, such as overstating the efficacy of therapeutic interventions, misrepresenting credentials, or making unfounded assertions about treatment outcomes.

One pertinent example involves LPCs who may claim that their therapeutic methods guarantee specific outcomes, such as complete resolution of mental health issues within a predetermined timeframe. This type of claim is misleading and unsupported by empirical evidence, as therapeutic outcomes can vary widely among individuals.

Research indicates that exaggerated claims in health-related contexts can misinform the public and lead to unrealistic expectations regarding treatment efficacy (Bratton et al., 2019; Sumner et al., 2016). Such practices can erode trust in the counseling profession and violate ethical standards set forth in the TAC.

Another example of exaggerated claims can be found in LPCs who assert that their qualifications or experiences are superior to those of their peers without substantiating such claims. This is particularly concerning in a field where the perception of competence can significantly influence client choices. Studies have shown that exaggeration in professional credentials can lead to a loss of public trust, as it creates a false narrative about the provider's capabilities (Shyagali et al., 2022).

The TAC explicitly prohibits LPCs from making misleading statements about their qualifications, emphasizing the importance of honesty in professional representation. Moreover, LPCs may sometimes engage in "spin" by presenting their services in a manner that suggests they are more effective than they are in reality. For instance, a counselor might highlight only positive client testimonials while neglecting to mention cases where clients did not achieve desired outcomes. This selective reporting can create a skewed perception of the counselor's effectiveness, which is a violation of the ethical guidelines outlined in the TAC (Shyagali et al., 2022).

The implications of such exaggerations are profound, as they can lead clients to make ill-informed decisions regarding their mental health care.

Rule 681.41(b) states that these same requirements apply to statements the licensee makes about services provided by any mental health organization, agency, including, but not limited to, the effectiveness of services, qualifications, or products. For instance, a counselor may take pride in working for an employer that endorses CBT as their primary counseling modality. The counselor may have personally benefitted greatly from CBT and believe firmly in its use.

Despite the success of CBT and the research to validate its efficacy, it is still dependent on factors that frequently change; the motivation level of the client, or the ever-changing expertise of counselors, for example. To characterize an entire organization as effective or successful would be a highly difficult assertion to prove given all of the variables impacting such a claim.

Rulue 681.41 (c) and (d)

NOTE: Rules 681.41 (c) and (d) have been deleted in the BHEC/LPC Rulebook, March 24, 2025 edition with paragrapch (e) on Technology now moving up to paragraph (c).

The deleted paragraphs are worth noting:

[(c) A licensee must discourage a client from holding exaggerated or false ideas about the licensee's professional services, including, but not limited to, the effectiveness of the services, practice, qualifications, associations, or activities. If a licensee learns of exaggerated or false ideas held by a client or other person, the licensee must take immediate and reasonable action to correct the ideas held.]

[(d) A licensee must make reasonable efforts to discourage others whom the licensee does not control from making misrepresentations; exaggerated or false claims; or false, deceptive, or fraudulent statements about the licensee's practice, services, qualifications, associations, or activities. If a licensee learns of a misrepresentation; exaggerated or false claim; or false, deceptive, or fraudulent statement made by another, the licensee must take reasonable action to correct the statement.]

The reason given for the change is stated in the Preamble of the Texas Administrative Code:

Reasoned Justification.

The adopted amendments remove language identified during the quadrennial rule review as potentially unenforceable, while not changing the substantive requirement that a licensee not make or benefit from false, misleading, deceptive, fraudulent, or exaggerated claims.

List of interested groups or associations against the rule.

None.

Summary of comments against the rule.

Four individuals commented against the proposed rule, suggesting that it is important for license holders to correct misinformation when they learn of it. Several commenters mentioned the danger of false information appearing online, including fake online reviews.

List of interested groups or associations for the rule.

None.

Summary of comments for the rule.

One commenter supported the proposed amendment without comment.

Agency Response.

The agency appreciates the public comment. The proposed amendment will eliminate blanket language requiring a licensee to correct misrepresentations made by another person without any evidence of impact to the licensee or a client. However, Council rules will continue to prohibit a licensee from benefiting from any false, deceptive, or fraudulent statements, which would include having someone post false advertisements online. (From the Texas Register, Preamble, regarding Rule 681.41)

The Rule did not clearly distinguish between “other person” mentioned in the paragraph (c) and “others whom the licensee does not control” in paragraph (d), but it might be assumed that “other person” refered to those with whom the counselor had some control and influence, while “others whom the licensee does not control” would pertain to any other third party. Regardless, these two paragraphs have been deleted due to their difficulty to enforce.

Promoting Hope Without Misleading Statements

It is necessary to instill hope in clients. Although promoting hope is an integral part of a licensee’s role, it is important not to violate ethical standards through statements that assert outcomes for a specific client. Such statements are, in essence, unvalidated predictions of how the client will respond to treatment.

Avoiding statements that reach too far in promoting or claiming the benefit of counseling or a particular technique can be a challenge for even well-intentioned therapists who may be enthusiastic to help, have seen many individuals under their care respond favorably to counseling, who feel confident in their abilities, and want to convey hope that the client’s situation can improve with counseling.

Regardless of a counselor’s success with previous clients, there are many variables that make future results unpredictable. The benefits of counseling can be dependent on factors such as the skill of the counselor, the client’s investment in homework assignments, the client’s compatibility with, and confidence in the counselor, the client’s family support, other emerging or changing stressors faced by the client, among others.

These factors are unique for each client and invalidate absolute claims or predictions regarding a specific individual’s future success resulting from counseling interventions.

Statements like; “CBT has been effective in treating depression for many people” is an accurate claim, but; “I know you will get better with CBT,” is an unethical claim.

When clients question or report that a particular technique, or that counseling in general, is not working for them, counselors may be tempted to defend an approach with general evidence that may mislead the client to believe the approach is a guarantee of success for them personally.

In such situations, counselors can make statements like; “It has been my experience, and research demonstrates, that this approach has helped some people, but it doesn’t mean it will help you. We can wait to see if practicing some of the coping skills outside of our sessions will help, or we can try a different approach if you would like.” Or, depending on the situation, it might be time to suggest a referral to another counselor if the client suggests it or is not benefitting from treatment.

Rule 681.41 (c)

Technology

Rule 681.41 (c) states: “Technological means of communication may be used to facilitate the therapeutic counseling process.” This rule recognizes the evolving landscape of communication technology and its integral role in facilitating the therapeutic counseling process. This provision allows licensed counselors to embrace various technological means, such as video conferencing, online messaging, and telephonic consultations, to enhance the accessibility and efficiency of mental health services. By incorporating these tools, counselors can reach a broader audience, including individuals in remote areas or those with mobility challenges, thus breaking down barriers to access.

The use of technology in counseling not only expands service delivery options but also supports the therapeutic relationship between counselors and clients. When utilized effectively, these technological means can foster engagement and provide a comfortable environment for clients, especially those who may be apprehensive about traditional face-to-face interactions. However, the code emphasizes the importance of maintaining professional standards, ensuring confidentiality, and adhering to ethical guidelines. Counselors must be trained in the appropriate use of these technologies, ensuring that they safeguard client information and provide a secure platform for communication.